- Home

- Gerald Durrell

Catch Me a Colobus

Catch Me a Colobus Read online

Bello:

hidden talent rediscovered!

Bello is a digital only imprint of Pan Macmillan, established to breathe new life into previously published, classic books.

At Bello we believe in the timeless power of the imagination, of good story, narrative and entertainment and we want to use digital technology to ensure that many more readers can enjoy these books into the future.

We publish in ebook and Print on Demand formats to bring these wonderful books to new audiences.

About Bello:

www.panmacmillan.com/imprints/bello

About the author:

www.panmacmillan.com/author/geralddurrell

By Gerald Durrell

My Family and Other Animals

A Zoo in My Luggage

Birds, Beats and Relatives

Garden of the Gods

The Overloaded Ark

The Talking Parcel

The Mockery Bird

The Donkey Rustlers

Catch me A Colobus

Beasts In My Belfry

The New Noah

The Drunken Forest

The Whispering Land

Rosy is My Relative

Two in the Bush

Three Singles to Adventure

The Ark’s Anniversary

Golden Bats and Pink Pigeons

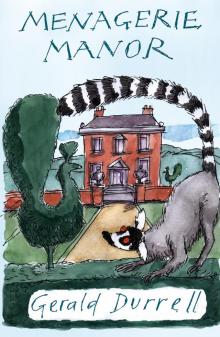

Menagerie Manor

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Bafut Beagles

Marrying off Mother and Other Stories

The Aye-Aye And I

Fillets of Plaice

Ark on the Move

Encounters with Animals

The Stationary Ark

Gerald Durrell

CATCH ME A COLOBUS

This book is for five stalwart members of my staff whose hard work, dedication and cheerfulness (even in moments of gloom and despondency) have helped me so much. Without their staunch backing I could have achieved little or nothing.

They are Catha Weller, Betty Boizard, Jeremy Mallinson, John (Shep) Mallet, and John (Long John) Hartley.

Contents

Author’s Note

1. Wash and Brush Up

2. Just Jeremy

3. A Lion in Labour

4. Mr and Mrs D

5. Leopards in the Lavatory

6. Catch Me a Colobus

7. Keep Me a Colobus

8. A Pageant of Births

9. Digging up Popocatepetl

10. Animals for Ever

A Message from the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust

Author’s Note

As the incidents in this book cover a period of about seven years and I have had to do a lot of pruning and grafting, some of them do not appear in the exact order in which they happened. This has been done purely to make the book run more smoothly, so if any of my readers notice that certain things are not necessarily in sequence they will understand why. My thanks are due to Messrs. Rupert Hart-Davis for permission to use the extract from Menagerie Manor on page 7.

Gerald Durrell

1. Wash and Brush Up

Dear Mr Durrell

I have frequently wondered about kangaroo pouches . . .

When I come back from an expedition abroad I always have a sense of great excitement at seeing the zoo again: the new cages that have been constructed in my absence from what had been mere drawings, the new animals that have arrived, the animals which have given birth; to be greeted by the discordant cries of joy from the various animals that recognise you and are pleased to see you back. Generally, it’s a very pleasant and exciting homecoming.

But on this occasion I had been on a fairly prolonged trip to Australia, New Zealand and Malaya, and on my return I found, to my consternation, that my precious zoo was looking shabby and unkempt. Not only that, but I soon discovered that it was almost bankrupt. After all the hard work and money that I had put into it, it was rather like being kicked in the solar plexus. Far from being able to relax after what had been a fairly hectic trip, I had to set to with the utmost rapidity to see what I could do to save the zoo.

The first thing I did, of course, was take over the management of the place myself, and then offer the job of Deputy Director to Jeremy Mallinson, who had been with the zoo since its inception. I knew of his immense integrity and of his deep love for the animals in his care. Moreover, he had worked in every section of the zoo and therefore knew most of the problems involved. To my infinite relief he accepted the job. Then I had a meeting with the heads of all the other sections and explained the situation to them. I said that it was more than likely that the zoo might have to close down, but, that if they were prepared to stay with me and work as hard as they could for a pittance, there was a good possibility that we might be able to pull it out of the mire. To their everlasting credit they all agreed to do this. So at least I knew that the animals would not suffer and would be well looked after.

My next job was to try and find a good administrative secretary. This was not as easy as it sounds. I advertised, and specified in the advertisement that a knowledge of shorthand, typing, and most important of all, bookkeeping, were essential. Somewhat to my surprise I got a flood of applicants. On interviewing them, I found that half a dozen of them couldn’t add two and two and make four, and very few of them knew what a typewriter even looked like. One young man even went so far as to say that he had applied for the job because he thought he could pick it up as he went along. After interviewing about twenty of these morons I was beginning to lose hope. Then we came to one Catha Weller. She waltzed into my office for her interview, diminutive, rotund, with sparkling green eyes and a comforting smile. She explained that her husband had just been transferred to Jersey and that she had had to give up her job in London, which she had had for the last seventeen years. Yes, she knew how to do bookkeeping, shorthand and typing – the lot. I looked at Jacquie and Jacquie looked at me. We both knew instinctively that a miracle had happened; we had found exactly what we wanted. So, within a few days, Catha Weller was installed, trying to make some sort of order out of the chaos of bookkeeping that had accumulated during my absence abroad.

The zoo, at that time, had two debts: one of twenty thousand pounds, which was the money that I had borrowed and which had been used for the original construction work, and a local overdraft and creditors amounting to another fourteen thousand pounds. My next problem, of course, was the difficult one of how to get sufficient finance to keep the zoo on an even keel in order that it should survive. This occupied me for some considerable time. During all this time Jeremy, being new to his job, had to keep coming to consult me about various animal problems, and Catha about various financial matters, all of which were new to her, and this, combined with the worry of trying to think of a way of saving the zoo, drove me into the very depths of depression. So, in spite of my protests, Jacquie called in our doctor.

‘I’m not ill,’ I protested. ‘It’s just worry. Can’t you give me a jab of something to keep me going?’

‘I’ll do better than that,’ said Mike. ‘I’ll give you some tablets to take.’

So he prescribed a bottle of rather lurid looking little capsules, of which I was supposed to take one a day. Little did he or I know that by doing this he was making the most important gesture towards saving the zoo.

Now two of our dearest and oldest friends on the island are Hope and Jimmy Platt. Jimmy spent most of his time in London, but Hope was a constant visitor to the zoo and would frequently pop up for a drink. She happen

ed to come up one evening when I had, quite by mistake, taken two of my tranquillisers instead of one. The result was that I looked and sounded as though I was in the last stages of inebriation. Hope is a large and formidable woman, and she frowned at me as I staggered across the room to greet her.

‘What’s the matter with you’ she inquired, with all the authority of fourteen stone. ‘Have you been hitting the bottle?’

‘No,’ I replied, ‘I wish I had. It’s these damned tranquillisers. I took two instead of one.’

‘Tranquillisers?’ said Hope, incredulously. ‘What on earth are you taking tranquillisers for?’

‘Sit down and let me get you a drink, and I’ll tell you all about it,’ I said.

So for the next hour I poured out my tale of woe to Hope. At the end of it she heaved herself massively out of the chair and stood up to go.

‘We’ll soon put a stop to this,’ she said firmly. ‘I’m not having you taking tranquillisers at your age. I’m going to see Jimmy about it.’

‘But, I don’t see why Jimmy should be worried . . .’ I began.

‘You listen to Mama,’ said Hope. ‘I’ll speak to Jimmy.’

And so she did. The next thing was a phone call from Jimmy. Would I please go round and see him and explain the matter. So I went round and told him how I had planned, originally, that once the zoo was self-supporting I was going to turn it into a Trust, but that it would be impossible to start a Trust carrying such an enormous debt. Jimmy agreed entirely, and sat brooding for a while.

‘Well there’s only one thing to be done,’ he said at last, ‘and that’s to launch a public appeal. First of all, I’ll give you two thousand pounds in order to tide you over your present difficulties, and I shall also contribute two thousand pounds to the appeal to encourage other people. If the appeal is a success, we can think again.’

To say that I was overwhelmed would be putting it mildly, and I went back to the zoo in a sort of daze. It really seemed as though there might be a chance of saving the place after all.

Launching an appeal is not quite as easy as it sounds. Neither is every appeal necessarily successful. But here our local paper, the Evening Post, which had always been our ally, gave us a most wonderful write-up about what we had done in the past, and explained our aims for the future. The appeal was launched and, in what seemed like a miraculously short space of time, we had raised twelve thousand pounds. I think the two donations that touched me most were the one from a small boy, of five shillings, which must have been his week’s pocket money, and another contribution of five pounds from the staff of the Jersey Zoo. This money was going to be the working capital of the Trust and therefore it could not be used for all the vital jobs that needed to be done in the zoo itself.

We now came to the second part of Jimmy’s stratagem. Both he and I agreed that the Trust could not be formed unless the matter of the original loan were cleared up. The Trust could then be launched with the twelve thousand pounds in hand, which would give it a good start, though still not good enough to allow for any large scale rebuilding or development. So I, personally, agreed to pay back the twenty thousand pounds owing to an increasingly restive bank out of my book royalties, and hand over the zoo and its contents to the Trust. This was done, and the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust came into being and officially took over the zoo, with myself acting as Honorary Director of both the Trust and the zoo. We chose a group of active people who were sympathetic towards our aims to act as our Council, and were delighted when Lord Jersey agreed to become our President. We chose, as our emblem, the Dodo, that large waddling pigeon-like bird that had once inhabited the island of Mauritius, and which was exterminated with great rapidity as soon as the island had been discovered. We felt that it symbolised the way in which a species can be wiped off the face of the earth in a remarkably short space of time by the thoughtlessness and greed of man.

But we were not out of the woods yet. It was still a very trying time, and I was still living on tranquillisers, unbeknownst to Hope Platt. For, at the same time as all this was going on, I was trying to write a book. This is a task that I view with abhorrence at the best of times, but now it was imperative, for I had twenty thousand pounds to pay back to the bank and the only way I could earn the money was by writing.

The book was called Menagerie Manor, and in it I explained why I wanted a zoo in the first place, and why I wanted the zoo eventually to become a Trust. I can do no better, I think, to explain it now than to quote what I wrote then:

‘I did not want a simple, straightforward zoo, with the ordinary run of animals: the idea behind my zoo was to aid in the preservation of animal life. All over the world various species are being exterminated or cut down to remnants of their former numbers by the spread of civilisation. Many of the larger species are of commercial or tourist value, and, as such, are receiving the most attention. Yet, scattered about all over the world, are a host of fascinating small mammals, birds and reptiles, and scant attention is being paid to their preservation, as they are neither edible nor wearable, and of little interest to the tourist who demands lions and rhinos. A great number of these are island fauna, and as such their habitat is small. The slightest interference with this, and they will vanish forever: the casual introduction of rats, say, or pigs could destroy one of these island species within a year. The obvious answer to this whole problem is to see that the creature is adequately protected in the wild state so that it does not become extinct, but this is often easier said than done. However, while pressing for this protection, there is another precaution that can be taken, and that is to build up under controlled conditions breeding stocks of these creatures in parks or zoos, so that, should the worst happen and the species become extinct in the wild state, you have, at least, not lost it forever. Moreover, you have a breeding stock from which you can glean the surplus animals and reintroduce them into their original homes at some future date. This, it has always seemed to me, should be the main function of any zoo, but it is only recently that the majority of zoos have woken up to this fact and tried to do anything about it. I wanted this to be the main function of my zoo.’

The problems of forming the Trust were greater and more complex than I had anticipated. They ranged from what subscription we should charge to members – not so large that people could not afford to become members, yet not so small that it would be of little benefit to us – down to details like what pamphlets we were going to publish to explain our aims and objects, and how these pamphlets were to be distributed. Over the years I have received a great number of letters about my books, and all of these had been answered and copies had been kept. So now all these people were circularised with a pamphlet and an enrolment form and, to my great delight, the vast majority of them joined the Trust immediately. When the new book, Menagerie Manor, was published it proved very popular (fortunately for me), and in it I asked any readers to join the Trust. So we got a fresh batch of members. By now we had some seven hundred and fifty Trust members dotted about in all parts of the world. It was particularly encouraging to think that people in countries as far away as Australia, South Africa and the United States were supporting a project which they might never even see.

At that time we were all working flat out for, although things were still fairly dicey, we could at least see, distantly on the horizon, some sign of success. To say that we were exhausted at the end of each day was an understatement. At that time I started receiving a spate of telephone calls, and these generally happened at the most irritating times. In the middle of lunch, for instance, I was called to the telephone – a long distance call from a woman in Torquay whose tortoise had just given birth to eggs. She wanted to know what to do with them. On another occasion, a woman wanted to know how to clip her budgerigar’s toenails. But the telephone call that really put the lid on it came at eleven o’clock one night when I was drowsing in front of the fire. It was a long distance call from

up north: a Lord McDougall wanted to speak to me. Thinking, in my innocence, that perhaps he wanted to give a large sum of money for the Trust, I asked the operator to put him through. When he came on the line it became immediately obvious that his lordship had imbibed wisely but in too great a quantity.

‘Ish that Durrell?’ he wanted to know.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘Now, you are the one man in England who can help me. I have a bird.’

I groaned inwardly. It was sure to be another budgerigar, I thought.

‘I own . . . a fleet of ships,’ he said, enunciating with great difficulty, ‘and one of my captains had thish . . . bird fly on board and he has jus’ brought it to me. Now . . . I want to know if you can help it?’

‘Well, what sort of bird is it?’ I inquired.

‘It’s a shweet little thing,’ he said.

As a zoological description this left much to be desired. ‘I mean, what sort of size or shape is it?’

‘Well . . . it’s a very shmall greyish-brown bird, with a whitish breast,’ he said. ‘Very tiny feet . . . very tiny feet . . . Remarkably tiny feet, in fact . . .’

‘I think it must be a Stormy Petrel,’ I said. ‘They do, quite frequently, fly on board ships.’

‘I will immediately charter a train and shend it to you if you can shave it,’ said his lordship lavishly.

I explained, at great length, that this would be quite useless. These tiny birds spend most of their lives at sea, feeding on minute forms of animal life, and are almost impossible to keep in captivity. In any case, even if he did send the bird to me, by the time it arrived it would most assuredly be dead.

‘I will shpare no expenshe whatshoever,’ said his lordship.

At that moment the telephone was torn from his grasp and a girl with a very county voice said, ‘Mr Durrell?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

A Zoo in My Luggage

A Zoo in My Luggage The New Noah

The New Noah The Bafut Beagles

The Bafut Beagles Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Catch Me a Colobus

Catch Me a Colobus Menagerie Manor

Menagerie Manor The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Ark on the Move

Ark on the Move My Family and Other Animals

My Family and Other Animals Two in the Bush (Bello)

Two in the Bush (Bello) The Stationary Ark

The Stationary Ark The Whispering Land

The Whispering Land Three Singles to Adventure

Three Singles to Adventure Fillets of Plaice

Fillets of Plaice The Aye-Aye and I

The Aye-Aye and I Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons

Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons The Drunken Forest

The Drunken Forest Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories

Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy)

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) The Corfu Trilogy

The Corfu Trilogy Marrying Off Mother

Marrying Off Mother Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush