- Home

- Gerald Durrell

Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Read online

GERALD DURRELL

Encounters with Animals

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

Ralph Thompson

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

Introduction

PART ONE: BACKGROUND FOR ANIMALS

The Black Bush

Lily-Trotter Lake

PART TWO: ANIMALS IN GENERAL

Animal Courtships

Animal Architects

Animal Warfare

Animal Inventors

Vanishing Animals

PART THREE: ANIMALS IN PARTICULAR

Animal Parents

The Bandits

Wilhelmina

Adopting an Anteater

Portrait of Pavlo

PART FOUR: THE HUMAN ANIMAL

MacTootle

Sebastian

PENGUIN BOOKS

ENCOUNTERS WITH ANIMALS

Gerald Durrell was born in Jamshedpur, India, in 1925. He returned to England in 1928 before settling on the island of Corfu with his family. In 1945 he joined the staff of Whipsnade Park as a student keeper, and in 1947 he led his first animal-collecting expedition to the Cameroons. He later undertook numerous further expeditions, visiting Paraguay, Argentina, Sierra Leone, Mexico, Mauritius, Assam and Madagascar. His first television programme, Two in the Bush, which documented his travels to New Zealand, Australia and Malaya was made in 1962; he went on to make seventy programmes about his trips around the world. In 1959 he founded the Jersey Zoological Park, and in 1963 he founded the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust. He was awarded the OBE in 1982. Encouraged to write about his life’s work by his novelist brother Lawrence, Durrell published his first book, The Overloaded Ark, in 1953. It soon became a bestseller and he went on to write thirty-six other titles, including My Family and Other Animals, The Bafut Beagles, Encounters with Animals, The Drunken Forest, A Zoo in My Luggage, The Whispering Land, Menagerie Manor, The Amateur Naturalist and The Aye-Aye and I. Gerald Durrell died in 1995.

For

EILEEN MOLONY

In memory of late scripts, deep sighs

and over-long announcements

Introduction

During the past nine years, between leading expeditions to various parts of the world, catching a multitude of curious creatures, getting married, having malaria and writing several books, I made a number of broadcasts on different animal subjects for the B.B.C. As a result of these I had many letters asking for copies of the scripts. The simplest way of dealing with this problem was to amass all the various talks in the form of a book, and this I have now done.

That the original talks were at all popular is entirely due to the producers I have had, and in particular Miss Eileen Molony, to whom this book is dedicated. I shall always remember her tact and patience during rehearsals. In a bilious green studio, with the microphone leering at you from the table like a Martian monster, I am never completely at ease. So it was Eileen’s unenviable task to counteract the faults in delivery that these nerves produced. I remember with pleasure her voice coming over the intercom. with such remarks as: ‘Very good, Gerald, but at the rate you’re reading it will be a five-minute talk, not a fifteen-minute one.’ Or, ‘Try to get a little enthusiasm into your voice there, will you? It sounds as if you hated the animal … and try not to sigh when you say your opening sentence … you nearly blew the microphone away, and you’ve no idea how lugubrious it sounded.’ Poor Eileen suffered much attempting to teach me the elements of broadcasting, and any success I have achieved in this direction has been entirely due to her guidance. In view of this, it seems rather uncharitable of me to burden her with the dedication of this book, but I know of no other way of thanking her publicly for her help. And anyway, I don’t expect her to read it.

I am constantly being surprised by the number of people, in different parts of the world, who seem to be quite oblivious to the animal life around them. To them the tropical forests or the savannah or the mountains in which they live are apparently devoid of life. All they see is a sterile landscape. This was brought home most forcibly to me when I was in Argentina. In Buenos Aires I met a man, an Englishman who had spent his whole life in Argentina, and when he learnt that my wife and I intended to go out into the pampa to look for animals he stared at us in genuine astonishment.

‘But, my dear chap, you won’t find anything there,’ he exclaimed.

‘Why not?’ I inquired, rather puzzled, for he seemed an intelligent person.

‘But the pampa is just a lot of grass,’ he explained, waving his arms wildly in an attempt to show the extent of the grass, ‘nothing, my dear fellow, absolutely nothing but grass punctuated by cows.’

Now, as a rough description of the pampa this is not so very wide of the mark except that life on this vast plain does not consist entirely of cows and gauchos. Standing in the pampa you can turn slowly round and on all sides of you, stretching away to the horizon, the grass lies flat as a billiard-table, broken here and there by the clumps of giant thistles, six or seven feet high, like some extraordinary surrealist candelabra. Under the hot blue sky it does seem to be a dead landscape, but under the shimmering cloak of grass, and in the small forests of dry, brittle thistle-stalks the amount of life is extraordinary. During the hot part of the day, riding on horseback across the thick carpet of grass, or pushing through a giant thistle-forest so that the brittle stems cracked and rattled like fireworks, there was little to be seen except the birds. Every forty or fifty yards there would be burrowing owls, perched straight as guardsmen on a tussock of grass near their holes, regarding you with astonished frosty-cold eyes, and, when you got close, doing a little bobbing dance of anxiety before taking off and wheeling over the grass on silent wings.

Inevitably your progress would be observed and reported on by the watchdogs of the pampa, the black-and-white spur-winged plovers, who would run furtively to and fro, ducking their heads and watching you carefully, eventually taking off and swooping round and round you on piebald wings, screaming ‘Tero-tero-tero … tero … tero,’ the alarm cry that warned everything for miles around of your presence. Once this strident warning had been given, other plovers in the distance would take it up, until it seemed as though the whole pampa rang with their cries. Every living thing was now alert and suspicious. Ahead, from the skeleton of a dead tree, what appeared to be two dead branches would suddenly take wing and soar up into the hot blue sky: chimango hawks with handsome rust-and-white plumage and long slender legs. What you had thought was merely an extra-large tussock of sun-dried grass would suddenly hoist itself up on to long stout legs and speed away across the grass in great loping strides, neck stretched out, dodging and twisting between the thistles, and you realized that your grass tussock had been a rhea, crouching low in the hope that you would pass it by. So, while the plovers were a nuisance in advertising your advance, they helped to panic the other inhabitants of the pampa into showing themselves.

Occasionally you would come across a ‘laguana’, a small shallow lake fringed with reeds and a few stunted trees. Here there were fat green frogs, but frogs which, if molested, jumped at you with open mouth, uttering fearsome gurking noises. In pursuit of the frogs were slender snakes marked in grey, black and vermilion red, like old school ties, slithering through the grass. In the rushes you would be almost sure to find the nest of a screamer, a bird like a great grey turkey: the youngster crouching in the slight depression in the sun-baked ground, yellow as a buttercup, but keeping absolutely still even when your horse’s legs straddled it, while its parents paced frantically about, giving plaintive trumpeting cries of anxiety, intermixed with softer instructions to their chick.

This was the pampa during the day. In the evening, as you rode homeward, t

he sun was setting in a blaze of coloured clouds, and on the laguanas various ducks were flighting in, arrowing the smooth water with ripples as they landed. Small flocks of spoonbills drifted down like pink clouds to feed in the shallows among snowdrifts of black-necked swans.

As you rode among the thistles and it grew darker you might meet armadillos, hunched and intent, trotting like strange mechanical toys on their nightly scavenging; or perhaps a skunk who would stand, gleaming vividly black and white in the twilight, holding his tail stiffly erect while he stamped his front feet in petulant warning.

This, then, was what I saw of the pampa in the first few days. My friend had lived in Argentina all his life and had never realized that this small world of birds and animals existed. To him the pampa was ‘nothing but grass punctuated by cows’. I felt sorry for him.

The Black Bush

Africa is an unfortunate continent in many ways. In Victorian times it acquired the reputation of being the Dark Continent, and even today, when it contains modern cities, railways, macadam roads, cocktail bars and other necessary adjuncts of civilization, it is still looked upon in the same way. Reputations, whether true or false, die hard, and for some reason a bad reputation dies hardest of all.

Perhaps the most maligned area of the whole continent is the West Coast, so vividly described as the White Man’s Grave. It has been depicted in so many stories – quite inaccurately – as a vast, unbroken stretch of impenetrable jungle. If you ever manage to penetrate the twining creepers, the thorns and undergrowth (and it is quite surprising how frequently the impenetrable jungle is penetrated in stories), you find that every bush shakes and quivers with a mass of wild life waiting its chance to leap out at you: leopards with glowing eyes, snakes hissing petulantly, crocodiles in the streams straining every nerve to look more like a log of wood than a log of wood does. If you should escape these dangers there are always the savage native tribes to give the unfortunate traveller the coup de grâce. The natives are of two kinds, cannibal and non-cannibal: if they are cannibal, they are always armed with spears; if non-cannibal, they are armed with arrows whose tips drip deadly poison of a kind generally unknown to science.

Now, no one minds giving an author a bit of poetic licence, provided it is recognizable as such. But unfortunately the West Coast of Africa has been libelled to such an extent that anyone who tries to contradict the accepted ideas is branded as a liar who has never been there. It seems to me a great pity that an area of the world where you find Nature at its most bizarre, flamboyant and beautiful should be so abused, though I realize that I am a voice crying rather plaintively in the wilderness.

My work has enabled me, one way and another, to see quite a lot of tropical forest, for when you collect live wild animals for a living you have to go out into the so-called impenetrable jungle and look for them. They do not, unfortunately, come to you. It has been brought home to me that in the average tropical forest there is an extraordinary lack of wild life: you can walk all day and see nothing more exciting than an odd bird or butterfly. The animals are there, of course, and in rich profusion, but they very wisely avoid you, and in order to see or capture them you have to know exactly where to look. I remember once, after a six months’ collecting trip in the forests of the Cameroons, that I showed my collection of about one hundred and fifty different mammals, birds and reptiles to a gentleman who had spent some twenty-five years in that area, and he was astonished that such a variety should have been living, as it were, on his doorstep, in the forest he had considered uninteresting and almost devoid of life.

In the pidgin-English dialect spoken in West Africa, the forest is called the Bush. There are two kinds of Bush: the area that surrounds a village or a town and which is fairly well trodden by hunters and in some places encroached on by farmland. Here the animals are wary and difficult to see. The other type is called the Black Bush, areas miles away from the nearest village, visited by an odd hunter only now and then; and it is here, if you are patient and quiet, that you will see the wild life.

To catch animals, it is no use just scattering your traps wildly about the forest, for, although at first the movements of the animals seem haphazard, you very soon realize that the majority of them have rooted habits, following the same paths year in and year out, appearing in certain districts at certain times when the food supply is abundant, disappearing again when the food fails, always visiting the same places for water. Some of them even have special lavatories which may be some distance away from the place where they spend most of their lives. You may set a trap in the forest and catch nothing in it, then shift that trap three yards to the left or right on to a roadway habitually used by some creature; and thus make your capture at once. Therefore, before you can start on your trapping, you must patiently and carefully investigate the area around you, watching to see which routes are used through the tree-tops or on the forest floor; where supplies of wild fruit are ripening; and which holes are used as bedrooms during the daytime by the nocturnal animals. When I was in West Africa I spent many hours in the Black Bush, watching the forest creatures, studying their habits, so that I would find it more easy to catch and keep them.

I watched one such area over a period of about three weeks. In the Cameroon forests you occasionally find a place where the soil is too shallow to support the roots of the giant trees, and here their place has been taken by the lower growth of shrubs and bushes and long grass which manages to exist on the thin layer of earth covering a grey carapace of rock beneath. I soon found that the edge of one of these natural grassfields, which was about three miles from my camp, was an ideal place to see animal life, for here there were three distinct zones of vegetation: first, the grass itself, five acres in extent, bleached almost white by the sun; then surrounding it a narrow strip of shrubs and bushes thickly entwined with parasitic creepers and hung with the vivid flowers of the wild convolvulus; and finally, behind this zone of low growth, spread the forest proper, the giant tree-trunks a hundred and fifty feet high like massive columns supporting the endless roof of green leaves. By choosing your vantage-point carefully you could get a glimpse of a small section of each of these types of vegetation.

I would leave the camp very early in the morning; even at that hour the sun was fierce. Leaving the camp clearing, I then plunged into the coolness of the forest, into a dim green light that filtered through the multitude of leaves above. Picking my way through the gigantic tree-trunks, I moved across the forest floor, so thickly covered with layer upon layer of dead leaves that it was as soft and springy as a Persian carpet. The only sounds were the incessant zithering of the millions of cicadas, beautiful green-and-silver insects that clung to the bark of the trees, making the air vibrate with their cries, and when you approached too closely zooming away through the forest like miniature aeroplanes, their transparent wings glittering as they flew. Then there would be an occasional plaintive ‘whowee’ of some small bird which I never managed to identify, but which always accompanied me through the forest, asking questions in its soft liquid tones.

In places there would be a great gap in the roof of leaves above, where some massive branch had perhaps been undermined by insects and damp until it had eventually broken loose and crashed hundreds of feet to the forest floor below, leaving this rent in the forest canopy through which the sunlight sent its golden shafts. In these patches of brilliant light you would find butterflies congregating: large ones with long, narrow, orange-red wings that shone against the darkness of the forest like dozens of candle flames; delicate little white ones like snowflakes would rise in clouds about my feet, then drift slowly back on to the dark leaf-mould, pirouetting as they went. Eventually I reached the banks of a tiny stream which whispered its way through the water-worn boulders, each wearing a cap of green moss and tiny plants. This stream flowed through the forest, through the rim of short growth and out into the grassfield. Just before it reached the edge of the forest, however, the ground sloped and the water flowed over a series of miniatur

e waterfalls, each decorated with clumps of wild begonias whose flowers were a brilliant waxy yellow. Here, at the edge of the forest, the heavy rains had gradually washed the soil from under the massive roots of one of the giant trees, which had crashed down and now lay half in the forest and half in the grassfield, a great hollow, gently rotting shell, thickly overgrown with convolvulus, moss, and with battalions of tiny toadstools marching over its peeling bark. This was my hideout, for in one part of the trunk the bark had given way and the hollow interior lay revealed, like a canoe, in which I could sit well hidden by the low growth. When I had made sure that the trunk had no other occupant I would conceal myself and settle down to wait.

For the first hour or so there would be nothing – only the cries of cicadas, an occasional trill from a tree-frog on the banks of the stream, and sometimes a passing butterfly. Within a short time the forest would have forgotten and absorbed you, and after an hour, if you kept still, you would be accepted just as another, if rather ungainly, part of the scenery.

Generally, the first arrivals were the giant plantain-eaters who came to feed on the wild figs which grew round the edge of the grassfield. These huge birds, with long, dangling magpie-like tails, would give notice of their arrival when they were half a mile or so away in the forest, by a series of loud, ringing and joyful cries … caroo, coo, coo, coo. They would appear, flying swiftly from the forest with a curious dipping flight, and land in the fig-trees, shouting delightedly to each other, flipping their long tails so that their golden-green plumage gleamed iridescently. They would run along the branches in a totally unbirdlike way and leap from one branch to another with great kangaroo jumps, plucking off the wild figs and gulping them down. The next arrivals to the feast would be a troop of Mona monkeys, with their russet-red fur, grey legs, and the two strange, vivid white patches like giant thumbprints on each side of the base of the tail. To hear the monkeys approaching sounded like a sudden wind roaring and rustling through the forest, but if you listened carefully you would hear in the background a peculiar sort of whoop-whoop noise followed by loud and rather drunken honkings, like a fleet of ancient taxicabs caught in a traffic jam. This was the sound of the hornbills, birds who always followed the monkey troops around, feeding not only on the fruit that the monkeys discovered but also on the lizards, tree-frogs and insects that the movements of the monkeys through the tree-tops disturbed.

A Zoo in My Luggage

A Zoo in My Luggage The New Noah

The New Noah The Bafut Beagles

The Bafut Beagles Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Catch Me a Colobus

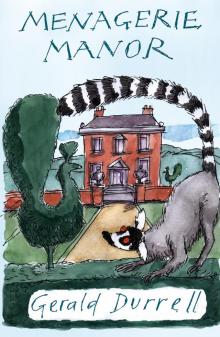

Catch Me a Colobus Menagerie Manor

Menagerie Manor The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Ark on the Move

Ark on the Move My Family and Other Animals

My Family and Other Animals Two in the Bush (Bello)

Two in the Bush (Bello) The Stationary Ark

The Stationary Ark The Whispering Land

The Whispering Land Three Singles to Adventure

Three Singles to Adventure Fillets of Plaice

Fillets of Plaice The Aye-Aye and I

The Aye-Aye and I Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons

Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons The Drunken Forest

The Drunken Forest Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories

Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy)

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) The Corfu Trilogy

The Corfu Trilogy Marrying Off Mother

Marrying Off Mother Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush