- Home

- Gerald Durrell

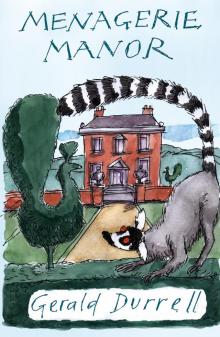

Menagerie Manor Page 13

Menagerie Manor Read online

Page 13

Jacquie and I went down to the market in St Helier and there we walked among the multi-coloured stalls that surround the charming, Victorian fountain with its plaster cherubim, its palms and its maidenhair fern and its household cavalry – the plump scarlet goldfish. It was difficult to know what to choose for N’Pongo that would tempt his appetite, for he had such an excellent variety of food in his normal diet. So we bought out-of-season delicacies that cost us a small fortune. Then, when we were loaded down with exotic fruits and vegetables, I suddenly noticed on a stall that we were passing an immense green and white water melon. Water melon is not to everyone’s taste, but I personally prefer it to ordinary melon. It occurred to me that the bright pink-coloured, scrunchy, watery interior with its glossy black seeds might be something that would appeal to N’Pongo, for, as far as I knew, he had never sampled it before. We added the gigantic melon to our loads and drove back to the Zoo.

By now, through lack of food and drink, N’Pongo was in a very bad way. Jeremy had managed to persuade him to drink a little skimmed milk by the subterfuge of rubbing a Disprin on his gums. The Disprin, of course, dissolved rapidly and the taste not being to his liking, N’Pongo was only too happy to take a couple of gulps of the milk to wash out his mouth. One by one we presented him with the things we had obtained in the market, and one by one he viewed them with an apathetic glance and refused the hothouse grapes, the avocado pears and other delicacies. Then we cut him a slice of water melon, and for the first time he displayed signs of interest. He prodded the slice with his finger and then leant forward and smelt it carefully. The next minute he had the slice in his hands, and to our great delight had started to eat. But we did not become too jubilant, for we knew that the water melon contained practically no nutriment, but at least it had aroused his interest in food again. The next thing was to try to administer an antibiotic, as by now the consensus of expert opinion was that he was suffering from a form of colitis. Since he still refused to take any quantity of liquid in which we could mix medicines, there was only one way to get the antibiotic into him, and that was by injection.

We enticed N’Pongo out of his cage and kept Nandy shut up; he would be sufficiently difficult to deal with, in spite of his emaciated condition, without having any assistance from his, by now, extremely powerful wife. He squatted on the floor of the Mammal House, staring about him with dull, sunken eyes. Jeremy squatted one side of him, with a supply of water melon to try to maintain his interest, while I on the other side hastily prepared the syringe for the injection. N’Pongo watched my preparations with a mild interest and once put out his hand gently to try to touch the syringe. When I was ready, Jeremy endeavoured to distract his attention with pieces of water melon, and as soon as his head was turned away from me I pushed the needle into his thigh and pressed the plunger home. N’Pongo gave no sign of having even noticed this. He followed us obediently back into his cage and, with a small piece of water melon, retired to his shelf where he curled up on his side, his arms folded, and stared at the wall. The following morning he showed very slight signs of improvement, and using the same subterfuge we managed to give him another injection. For the rest of the day there seemed no change in him, and although he ate some of the melon and drank a little skimmed milk he did not show any radical signs of progress.

I was now in a quandary: in 24 hours’ time I was due to leave for France. There I had organised and stirred up a bees’ nest of helpers and advisers. The BBC were also under the impression that the trip was a foregone conclusion. If I put it off at this juncture, I would have put a tremendous amount of people to a lot of trouble for nothing, and yet I felt I could not leave N’Pongo unless I was satisfied that he was either on the mend or else beyond salvation.

Then, the day before I was due to leave, he suddenly turned the corner. He started drinking his Complan – a highly concentrated form of dried milk – and eating a variety of fruits. By the evening of that day he showed considerable signs of improvement and had eaten quite a bit of food. The next morning I went down very early to look at him, for I was due to catch my plane to Dinard at 8.30. He was sitting up on the shelf, and although he still looked emaciated and unwell his eyes had a sparkle in them that had been lacking for the past few days. He ate quite well and drank his Complan, and I felt that he was at last on the road to recovery. I drove down to the airport and caught the plane to Dinard, and we motored down to the South of France. It cost a small fortune in trunk-calls to Jersey to keep myself apprised of N’Pongo’s progress, but, every time I telephoned, the reports got better and better, and when Jeremy informed me that N’Pongo had drunk one pint of Complan and eaten three slices of water melon, two bananas, one apricot, three apples and the white of eight eggs, I knew there was no further cause for alarm.

By the time I returned from France, N’Pongo had put on all the weight he had lost, and when I went into the Mammal House there he was to greet me, his old self: massive, black and rotund, his eyes glittering mischievously as he tried to inveigle me close enough to the wire so that he would pull the buttons off my coat. I reflected, as I watched him rolling on his back and clapping his hands vigorously in an effort to attract my attention, that, though it was delightful to have creatures like this – and of vital importance that they should be kept and bred in captivity – it was a two-edged sword, for the anxiety you suffered when they became ill made you wonder why you started the whole thing in the first place.

CHAPTER EIGHT

ANIMALS IN TRUST

Dear Mr Durrell,

You will probably be astonished to receive a letter from a complete stranger...

The Zoo has now been in existence for five years. During that time we have worked steadily towards our aim of building up our collection of those animals which are threatened with extinction in the wild state. Examples of these are our chimpanzees, a pair of South American tapirs, but, perhaps, the pair of gorillas are one of the most important of our acquisitions and one of which we are extremely proud. Apart from these, we have over the past year obtained a number of valuable creatures. It is not always possible to buy or collect these animals, so recently in exchange for an ostrich we had our binturong, a strange, small, bear-like animal with a long prehensile tail, which comes from the Far East; and a spectacled bear, whom we have christened Pedro.

Spectacled bears are the only members of the family to be found in South America, inhabiting a fairly restricted range high in the Andes. They are a blackish brown colour with fawn or cinnamon spectacled markings round the eyes and short waistcoats of a similar colour. They grow to be as large as the ordinary black bear, but Pedro, when he arrived, was still quite a baby and only about the size of a large retriever. We soon found that he was ridiculously tame and liked nothing better than to have his paws held through the bars while he munched chocolate in vast quantities. He is an incredible pansy in many ways, and several of the attitudes he adopts – one foot on a log while he leans languidly against the bars of his cage, with his front paws dangling limply – remind one irresistibly of the more vapid and elegant young men one can see at cocktail parties. He very soon discovered that if he did certain tricks the flow of chocolates and sweets increased a hundredfold, and so he taught himself to do a little dance. This consisted of standing on his hind legs and bending over backwards as far as he could, without actually falling, and then revolving slowly – a sort of backward waltz. This never failed to enchant his audience. To give him something with which to amuse himself, we hung a large empty barrel from the ceiling of his cage, having knocked both ends out of it: this formed a sort of circular swing and gave Pedro a lot of pleasure. He would gallop round the barrel and then dive head first into it, so that it swung to and fro vigorously. Occasionally, he would dive a bit too strenuously and come shooting out of the other end of the barrel and land on the ground. At other times, when he was feeling in a more soulful mood, he would climb into his barrel and just lie there, sucking his paws and humming to himself, an astonishingly loud v

ibrant hum as though the barrel contained quite a large dynamo.

Pedro was, at first, in temporary quarters, but, as we hoped to get him a mate eventually, we had to build him a new cage. During the period while his old quarters were being demolished and his new one being erected, he was confined in a large crate to which, at first, he took grave exception. However, when we moved it next to one of the animal kitchens and the fruit store, he decided that life was not so bad after all. The staff were constantly in view and nobody passed his crate without pushing a titbit to him through the bars. Then, two days before he was due to be moved into his new home, it happened. Jacquie and I were up in the flat, having a quiet cup of tea with a friend, when the intercommunication crackled and Catha’s voice, as imperturbable as though she were announcing the arrival of the postman, said:

‘Mr Durrell, I thought you would like to know Pedro is out.’

Now, although Pedro had been small when he arrived, he had grown with surprising rapidity and was now quite a large animal. Also, although he still appeared ridiculously tame, bears, I am afraid, are some of the few creatures in this world which you cannot trust in any circumstance. So, to say that I was alarmed by this news would be putting it mildly. I fled downstairs and out of the back door. Here, where the animal kitchen and fruit store form an annexe with a flat roof, I saw Pedro. He was galloping up and down on the roof, obviously having the time of his life. The unfortunate thing was that one of the main windows of the flat overlooked this roof, and if he went through that he could cause a considerable amount of havoc in our living quarters. Pedro was plainly unfamiliar with the substance called glass, and, as I watched, he bounded up to the window, reared up on his hind legs and hurled himself hopefully forward. It was lucky that it was an old-fashioned sash window with small panes of glass, and this withstood his onslaught. If it had been one big sheet of glass, he would have gone straight through it and probably cut himself badly. But with a slightly astonished expression on his face he rebounded from it: what appeared to be a perfectly good means of getting into the flat was barred by some invisible substance. I rushed round to where the crate was, in an endeavour to lift up the sliding door which, as always happens in moments of this sort of crisis, stuck fast. Pedro came and peered at me over the edge of the roof and obviously thought that he should come down to my assistance, but the long drop made him hesitate. I was still struggling with the door of the cage when Shep appeared with a ladder.

‘We’ll never get him down without this,’ he said, ‘he’s frightened to jump.’

He placed the ladder against the wall, while I continued my struggles with the door of the crate. Then Stefan came on the scene and was coming to my aid, when Pedro suddenly discovered the ladder. With a little ‘whoop’ of joy, he slid down it like a circus acrobat and landed in an untidy heap at Stefan’s feet.

Now, Stefan was completely unarmed and so was I, but fortunately Stefan kept his head and did the right thing: he stood absolutely still. Pedro righted himself and, seeing Stefan standing next to him, gave a little grunt, reared up on his hind legs and placed his paws on Stefan’s shoulders, who went several shades whiter but still did not move. I looked round desperately for some sort of weapon with which I could hit Pedro, should this be a preliminary to an attack on Stefan. Pedro, however, was not interested in attacking anyone. He gave Stefan a prolonged and very moist kiss with his pink tongue and then dropped to all fours again and started galloping round and round the crate, like an excited dog. I was still trying ineffectually to raise the slide when Pedro made a miscalculation. In executing a particularly complicated and beautiful gambol, he rushed into the animal kitchen. It was the work of a second for Shep to slam the door, and we had our escapee safely incarcerated. Then we freed the reluctant slide and pushed the crate up to the kitchen, opened its door, and Pedro re-entered his quarters without any demur at all. Stefan vanished and had a strong cup of tea to revive himself. Two days later we released Pedro into his spacious new quarters, and it was a delight to watch him rushing about, investigating every corner of the new place, hanging from the bars, pirouetting in an excess of delight at finding himself in such a large area.

When owning a zoo, the question of Christmas, birthday and anniversary presents is miraculously solved: you simply give animals to each other. To any harassed husband who has spent long sleepless nights wondering what gift to present to his wife on any of these occasions, I can strongly recommend the acquisition of a zoo, for then all problems are answered. So, having been reminded by my mother, my secretary and three members of the staff that my twelfth wedding anniversary was looming dark and forbidding on the horizon, I sat down with a pile of dealers’ lists, to see what possible specimens I could procure that would have a two-fold value of both gladdening Jacquie’s heart and enhancing the Zoo. The whole subterfuge had this additional advantage: I could spend far more money than I would have done otherwise, without the risk of being nagged for my gross extravagance. So, after several mouth-watering hours with the lists, I eventually settled on two pairs of crowned pigeons, birds which I knew Jacquie had always longed to possess. They are the biggest of the pigeon family and certainly one of the most handsome, with their powder-blue plumage, and scarlet eyes and their great feathery crests. Nobody knows how they are faring in the wild state, but they seem to be shot pretty indiscriminately both for food and for their feathering, and it is quite possible, before many years have passed, that crowned pigeons will be on the danger list. I saw that at that precise moment the cheapest crowned pigeons on the market were being offered by a Dutch dealer. Fortunately, I have a great liking for Holland and its inhabitants, so I thought it would be as well if I went over personally to select the birds, for, as I argued to myself, it would enable me to choose the very finest specimens (and for a wedding anniversary, surely nothing but the best would do?), and at the same time give me a chance to visit some of the Dutch zoos which are, in my opinion, among the finest in the world. Having thus salved my conscience, I went across to Holland.

It was just unfortunate that the very morning I called at the dealers to choose the crowned pigeons, a consignment of orang-utans had arrived. This put me in an extremely awkward position. First, I have always wanted to have an orang-utan. Secondly, I knew that we could not possibly afford them. Thirdly, owing in part to this trade in these delicate and lovely apes, their numbers have been so decimated in the wild state that it is possible within the next ten years they may well become extinct. As an ardent conservationist what was I to do? I could not report the dealer to anyone, for the simple reason that now they had managed to reach Holland there was no law against him having them in his possession. I was in a quandary. I could either not even look at the apes and leave them to his tender mercies, or else I could, as it were obliquely, encourage a trade of which I strongly disapproved, by rescuing them.

By this time I was so worked up over the conservation aspect of this problem that the financial side of it had disappeared completely from my mind. Knowing full well what would happen, I went and peered into the crate containing the baby orang-utans and was immediately lost. They were both bald and oriental-eyed; the male, who was the slightly larger of the two, looked like a particularly malevolent Mongolian brigand, while the female had a sweet and rather pathetic little face. As usual, they had great pot-bellies, owing to the ridiculous diet of rice on which the hunters and dealers insist on feeding them and which does them no good whatsoever, except to distend their stomachs and give them internal disorders.

They crouched in the straw, locked in each others arms; to each the other was the one recognisable and understandable thing in a horrifying and frightening world. They both looked healthy, apart from their distended tummies, but they were so young I knew the chances of their survival were risky. The sight of them, however, clutching each other and staring at me with such obvious terror, decided me, and (knowing that I should never hear the end of it) I sat down and wrote out a cheque.

That evening I telep

honed the Zoo to tell Jacquie that all was well and that I had not only managed to buy the crowned pigeons she wanted, but also two pairs of very nice pheasants. On hearing this, both Catha and Jacquie said that I should not be allowed to go shopping in animal dealers by myself and I had no sense of economy and why was I buying pheasants when I knew the Zoo could not afford them, to which I replied that they were rare pheasants and that was sufficient excuse. I then carelessly mentioned that I had also bought something else.

What, they inquired suspiciously, had I bought?

‘A pair of orang-utans,’ I said airily.

‘Orang-utans?’ said Jacquie. ‘You must be mad. How much did they cost? Where are we going to keep them? You must be out of your mind.’

Catha, on being told the news, agreed with her. I explained that the orang-utans were so tiny that they would practically fit in your pocket and that I could not possibly leave them to just die in a dealer’s shop in Holland.

A Zoo in My Luggage

A Zoo in My Luggage The New Noah

The New Noah The Bafut Beagles

The Bafut Beagles Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Catch Me a Colobus

Catch Me a Colobus Menagerie Manor

Menagerie Manor The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Ark on the Move

Ark on the Move My Family and Other Animals

My Family and Other Animals Two in the Bush (Bello)

Two in the Bush (Bello) The Stationary Ark

The Stationary Ark The Whispering Land

The Whispering Land Three Singles to Adventure

Three Singles to Adventure Fillets of Plaice

Fillets of Plaice The Aye-Aye and I

The Aye-Aye and I Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons

Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons The Drunken Forest

The Drunken Forest Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories

Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy)

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) The Corfu Trilogy

The Corfu Trilogy Marrying Off Mother

Marrying Off Mother Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush