- Home

- Gerald Durrell

The Stationary Ark Page 13

The Stationary Ark Read online

Page 13

In the second half of the seventeenth century we find John Aubrey writing: ‘Sir Bennet Hoskins, Baronet, told me that his keeper at his parks at Morehampton in Herefordshire, did for experiment sake, drive an iron nail thwert the hole of the woodpecker’s nest, there being a tradition that the damme will bring some leafe to open it. He layed at the bottome of the tree a cleane sheet, and before many houres passed the naile came out and he found a naile lying on the sheete. Quaere the shape or figure of the leafe. They say the moonewort will doe such things. This experiment may easily be tryed again.’

Such were the ideas of country gentlemen less than two hundred years ago. These educated men were curious, interested in experimentation, but casual as to method and credulous as to the result. John Ray replied forthrightly :

The story . . . is without doubt a fable, yet this eminent naturalist blamed the death of his daughter from jaundice on the use of newfangled scientific remedies instead of the old-fashioned cure – beer flavoured with horse manure.

Of course, since then, we have gained enormous knowledge of how animals behave and of the ecology of the world in general, but what we must realize is that, vast though our knowledge has become, it is still infinitesimal compared to what has to be learnt. Because we pluck a star out of the sky, it does not mean to say that we understand the universe.

Finally, I must say this: a record system is only as good as the people who devise it; it is the people who inherit it that must make it grow, graft on it, rearrange and nurture it and, where necessary, kill it and start again. The important thing about our record system is that everyone on the staff, qualified and unqualified, contributes his observations and so do all concerned with the day-to-day keeping of the animals. This is what makes their observations of such importance. It is clear that in a collection like this it is no use having a white-collar, office-bound scientist who only sees the animals once a month and relies almost entirely on other people’s observations. It must also be remembered that one must not work on the assumption that the people who contribute the data are omniscient. However desirable omniscience might be, it is not something acquired by experience, a religious upbringing or even a university education.

One can only go on the principle that, in the country of the blind, even a white stick is a start towards the acquisition of knowledge.

Pills, Potions and Palliatives

‘Weasels are said to be so skilled in medicine that, if by any chance their babies are killed, they can make them come alive again if they can get at them.’

T.H. White, The Books of Beasts

‘Violet most amiably knitted a small woollen frock for several of the fishes, and Slingsby administered some opium drops to them, through which kindness they became quite warm and slept soundly.’

Edward Lear

‘Herba Sacra. The “divine weed”, vervain, said by the old Romans to cure the bites of all rabid animals, to arrest the progress of venom, to cure the plague, to avert sorcery and witchcraft, to reconcile enemies, etc.’

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase & Fable

The discovery, identification and subsequent curing of an illness in animals is a task so fraught with difficulty that it might have made even the stout heart of Florence Nightingale quail. Imagine a patient who not only cannot tell you where the pain is, but, in many cases, takes great care to cover up all its symptoms; a patient who, having decided that you are trying to poison it, refuses all medication, regardless of how carefully embedded in meat, banana or chocolate it is; a patient who (because you cannot explain) interprets everything you do, from X-ray to injection, as a calculated assault on its life, its dignity, or both. With sick animals, you find that you have to have the patience of Job, the grim determination of Sisyphus, the duplicity of Judas, the strength of Samson, the luck of the devil and the bedside manner of Solomon before you can hope to achieve results.

A collecting expedition (where you have to be carpenter, dietician, cage cleaner, cook and veterinary surgeon to your animals) teaches you a lot about the basics of dealing with animals’ ills. When you have a collection of several hundred animals to look after and you are 140 miles away from the nearest settlement (which probably does not boast a doctor, let alone a vet) you have to develop your own approach. It does not, of course, have the delicate insouciance of Harley Street and, if the British Medical Association could see you at work, it is probable that you would never survive the strictures laid upon you.

After all, what respectable member of Harley Street would muffle a reluctant and, in consequence, greatly impassioned patient (in this case a mongoose) in an old plimsoll so as to give it an enema with a scent spray, purchased (in desperation) in the local native market? What dedicated Harley Street specialist would disrobe himself before an audience of some 200 fascinated Africans and prod himself all over with a hypodermic syringe, in order to persuade a highly suspicious (and immensely powerful) baboon that this was a most desirable and fashionable experience? What fastidious Harley Street man would consign himself, for the sake of his calling, to bed with a young chimpanzee (suffering from bronchitis) who spent the night trying to start gay romps, poking his finger in one’s eye, or urinating copiously, and with immense satisfaction, every half hour? What slick, sleek product of Guy’s, Bart’s, Edinburgh or University College is troubled by the danger that his patient may peck him up the left nostril while he is attending to a broken arm? This happened to me while I was setting a Tiger bittern’s wing, and the agony and resulting gory mess were hardly compensated for by the knowledge that the bird had missed. It was aiming for my eye.

I do not wish to seem harsh in my attitude towards the medical profession, but they really have a rather cushy job compared to someone who has to deal with animals. I defy any ordinary GP not to tear up his diploma when faced with thirtyseven monkeys, all suffering from acute diarrhoea brought on by an African animal boy feeding them Cascara tablets in place of their normal Brewers’ yeast: this ten minutes before you are due to put them on board a ship whose captain is notoriously anti-animal. But exhausting though this sort of training is, it gives you a good grounding in what to expect thereafter. And so, when you meet with a success in animal nursing, you are generally surprised and gratified.

The techniques for dealing with an animal in the back of beyond and dealing with one in a well-run zoo are similar, but not identical. For many years, there has been much argument in zoo circles as to the desirability of hospitals for animals. There are two schools of thought. The first maintains that a sick animal should be removed from its fellow creatures so as to prevent the spread of disease, to enable it to recover in hygienic surroundings and to ensure that the veterinarian dealing with it has it under the controlled conditions which are best from his point of view The second argues that, although a hospital may be necessary for providing the hygienic conditions needed for an operation, the psychological effect on the animal of its removal from familiar surroundings into unsympathetic and strange-smelling ones as well as the loss of its familiar human contacts and its being put in the charge of a stranger, is more detrimental than its quick return to unhygienic but familiar safe quarters. Of the two schools of thought I favour the second one. The effect of a serious illness on an animal is psychologically shattering in itself. Add to this the inevitable fear created by the process of medication or surgery, and add to that the removal of the creature from its own known and comforting territory and human contacts, and you are much more liable to have an animal which will panic or depress itself into death.

In the early stages of the Trust’s existence, the thorny question of whether or not to have a hospital was purely academic as far as we were concerned. We simply had not got the money to construct such a facility and therefore had to take a third line, which both schools of thought on the hospital problems tended to overlook. As we had not the wherewithal to create a hospital, it was up to us to try to eliminate, so fa

r as was possible, the need for one. That is to say, by spending what money we had on the provision of the best possible food and the most comfortable accommodation, we tried to practise what could be called a form of preventive medicine. To a large extent, we found that this does work. Our incidence of illness, considering the size and scope of the collection, has been extraordinarily light. But this is not to say that we have been totally free. We have had our quota of illnesses, epidemics and accidents from what the insurance companies (who always love laying the blame at other people’s doors) call ‘Acts of God’.

Our lack of facilities, however, did cause many problems for our long-suffering veterinary surgeons. A major abdominal operation is fraught with danger in any circumstances. To have to perform it in a place where you cannot provide perfect aseptic conditions makes things much worse. To keep your patient like that after the operation doubles your chances of failure.

Our first experience with this came when a lioness, who was almost ready to have her cubs, picked up a gas-forming organism. Naturally when she started her labour, it became impossible for her to give birth. We were in a difficult position, for the animal would take no anaesthetic by mouth and, at that stage in our career, we were so poor we could not afford the luxury of the Capchur-dart gun. The whole thing was made more difficult by the fact that it happened over a weekend. I had to get my friend, Oliver Graham-Jones, then the chief veterinary officer of London Zoo, to give up a pleasant weekend pottering round his prize rose bushes so as to fly to Jersey with his Capchur gun (he could not let anyone else do the job, as the police insisted that only he had a permit to use it). With the aid of our own veterinary surgeons the lioness was immobilized and we prepared for the Caesarean section. The operation took place in the open air part of the cage, with some old dentists’ spotlights set up for illumination. The operating table was striking in its simplicity: a well-scrubbed, ancient door on two trestles. It says much for the skill of our veterinary team that the already suppurating cubs (three of them) were removed and the lioness sterilized, with no complications of pneumonia or peritonitis, in spite of the fact that, after the operation, the zoo workshop had to double as a recovery hospital. Unhygienic though this operation was, however, it is necessary to point out that there are times when you can be too hygienic. If you scrub out your animal’s cage with disinfectant twice a day, disinfect its food, keep it carefully segregated from the public and wear mask and gloves yourself when in contact with it, the animal may thrive; but let one small, determined and unpleasant bug wriggle its way past your defences, and you will have a dead animal on your hands, for it will not have built up the resistance to counteract it.

A good example of this was the case of our two baby gorillas, Assumbo and Mamfe. The successful breeding of gorillas is still a sufficiently unusual occurrence to make the event notable and so these two – our first births – were treated with considerable reverence. Their nursery was most hygienic, their nappies hygienically washed, their food hygienically prepared, everyone who dealt with them or visited them wore masks and they were guarded from infection as if they were heirs to some holy dynasty. Then came the day when they had outgrown the incubator, the laundry-basket beds, the play-pen and, finally, the nursery itself; so they were transported in triumph down to the Mammal House, where a special cage had been prepared for them.

Almost immediately, Mamfe, the younger of the two, became ill. At first, he merely displayed a fluctuating interest in his food, a certain lethargy and a small weight loss. When this was accompanied by diarrhoea as well, Dr Carter, our local paediatrician, who had kept the infants under his care from birth, was sent an urgent call. His initial report (enshrined in our files and published in our Eleventh Annual Report) states that:

‘Examination at the time confirmed the lethargy and loss of appetite and he was not keen to play with Assumbo; however the tongue was clean although slightly dry; the throat was clear and no abnormality could be detected in the lungs. There was no evidence of any lymphadenopathy, the cervical, axillary and epitrochlear glands were all normal nor were the inguinal glands enlarged. Examination of the ears and throat showed no evidence of inflammation and urinalysis performed in the Laboratory showed no evidence of any urinary tract infection. Mamfe was treated empirically with Lomotil (Searle) 2.5 ml. three times per day (Diphenoxylate hydrochlor 2.5 mg. atropine sulph 0.025 mg. in 5 ml. suspension). It was noted that he tended to vomit after the administration of Lomotil and he was kept on clear fluids such as 5 per cent glucose solution and diluted SMA milk.’

However, the diarrhoea continued and when the laboratory report came through on faeces culture, it showed a pure growth of E. Coli. This is an unpleasant infection which can be a killer. The laboratory informed us cheerfully that it was sensitive to Chloramphenicol, Tetracycline, Streptomycin, Septrin and Neomycin, but this did not help much. It was a Saturday afternoon (why do animals always get sick at a weekend?) and there was great difficulty in getting a choice of antibiotics. Mamfe was therefore given Oxytetracydine, 125 mgs. in syrup, every six hours. This, to our increasing alarm, did not reduce, or stem, the diarrhoea. When Dr Carter came in on the Sunday, Mamfe was in bad condition and severely dehydrated. Dr Carter’s report continues:

‘He was listless and barely responded to human touch; his eyes were sunken and had a glazed appearance and he was disinterested in his surroundings and often did not appear to be focusing his eyes. The eyeballs were sunk into the sockets and he gave the typical appearance of a seriously dehydrated human baby. His tongue was dry and the skin on his abdomen was lax and when picked up between finger and thumb and then released, the elevated skin did not fall back as readily as normal. It was apparent that emergency measures were required to resuscitate the infant as soon as possible. When any restraint was used, he found reserves of strength. No attempts to give intravenous fluids could be made and so three different techniques were employed : -

(i) Intrahperitoneal transfusion. This method was described and used extensively by Carter (1953) in Africa as a method of rehydration for acutely dehydrated babies and the infants very rarely made more than a token protest at the procedure. However, Mamfe reacted very vigorously and by his continual shrieking, he raised his intrahabdominal pressure to such an extent that it was considered that the gut might be in danger of perforation by the needle. The needle was therefore withdrawn after 50 ml. of Hartmann’s solution had been administered and other routes were then used.

(ii) Sub-cutaneous infusion into the thighs. It was noted that Mamfe had very lax skin lying over the anteromedial aspects of his thighs and it was decided to try this method previously used extensively in paediatric practice in Children’s Hospitals, combined with hyaluronidase 150 oin. dissolved in 500 ml. Hartmann’s solution. It was found that 80 mls. of Hartmann’s solution could be injected with ease into the sub-cutaneous tissues in the antero-medial aspects of both thighs and it was quite astonishing to see the rate at which the fluid was absorbed in as much as it looked as if twice the quantity of fluid could have been administered in this way, if necessary.

(iii) Tube feeding. As Mamfe had not been troubled by vomiting apart from immediately after the administration of Lomotil, it was decided that this route should be attempted. It was calculated that he would require another 180 ml. of fluid to reach an approximate fluid balance in view of his state of dehydration. Miss J. Robbins, SRN, SCM, whose hospital duties routinely included tube feeding premature human babies, passed a gastric tube through the mouth with such speed and ease that Mamfe never even attempted to gag. 180 ml. of clear Hartmann’s solution was administered slowly by tube. In addition, Mamfe was given an intramuscular injection of Ampicillin 50 mgms. and Cloxacillin 25 mgms. in the form of Ampiclox (Beecham) six hourly for the following few days, and Miss Robbins instructed the staff at the zoo on the technique of tube feeding. Within a short time, the passing of the orohgastric tube was done without any difficulty whatsoever. Further therapy requi

red by Mamfe is given elsewhere, but dehydration had been successfully overcome and never became a problem thereafter.’

The infant gorilla, so plump and exuberant one minute and shrivelling away to nothing the next, was a sight not to be forgotten. Dr Carter told me that this was a fairly common occurrence in premature babies who, once they were removed from the carefully controlled environment of the intensive care unit into an ordinary ward, frequently became a prey to E.Coli and had little resistance to it.

Naturally you have to take all sensible precautions to prevent infection. Our policy is that every new arrival should be segregated while all possible tests on it are carried out, before it takes its place in the collection. By this means you minimize or eliminate the chance of introducing a sick animal. If the animal shows signs of disease, or of internal or external parasites which might contribute to disease, it undergoes treatment and is segregated, until it is no longer a danger. Thus we try to safeguard against a disease being introduced by a newcomer. It is for this reason that we have had to give up treating oiled or sick wild birds, for we found they were introducing parasitic infections through our defences. We now send them to the island’s equivalent of the RSPCA and give advice and help at long range, should it be necessary.

Quarantine periods and tests are our first line of defence, but we realize, ruefully, that this is not impregnable. Take the dreaded disease, aspergillosis, a virulent fungus that thrives in the lung cavities of birds and for which there is no known cure. There is a lot of evidence to show that a bird may live for years with a low grade infection of this without showing any signs. But should the bird undergo any stress, such as being caught up to be removed from one aviary to another or to be sent away, then the disease will flare up and kill the specimen in a short space of time. Owing to the fact that, in many instances, the disease is understandable, what appears to be a healthy bird will suddenly, for no apparent reason, die. Only on postmortem, does one find that its lungs are quite literally a fungus bed of infection. The chances of this happening with a newly arrived bird are, of course, considerable. As I have said elsewhere, one of the cock White-eared pheasants had this disease on arrival and died within twenty-four hours. With the White-eared pheasants we have bred in Jersey, we have had the same problem. We sent them away, apparently in tip-top condition, then heard that they had died of aspergillosis within twenty-four hours of arrival. Obviously they were infected before they left us, but showed no signs.

A Zoo in My Luggage

A Zoo in My Luggage The New Noah

The New Noah The Bafut Beagles

The Bafut Beagles Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Catch Me a Colobus

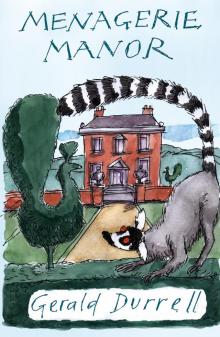

Catch Me a Colobus Menagerie Manor

Menagerie Manor The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Ark on the Move

Ark on the Move My Family and Other Animals

My Family and Other Animals Two in the Bush (Bello)

Two in the Bush (Bello) The Stationary Ark

The Stationary Ark The Whispering Land

The Whispering Land Three Singles to Adventure

Three Singles to Adventure Fillets of Plaice

Fillets of Plaice The Aye-Aye and I

The Aye-Aye and I Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons

Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons The Drunken Forest

The Drunken Forest Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories

Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy)

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) The Corfu Trilogy

The Corfu Trilogy Marrying Off Mother

Marrying Off Mother Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush