- Home

- Gerald Durrell

Catch Me a Colobus Page 16

Catch Me a Colobus Read online

Page 16

‘Then you’d better come and try and sort this one out,’ said Jacquie, acidly. ‘Apparently we’ve got the wrong papers for the Land Rover.’

‘Oh, God,’ I groaned. ‘Not again.’

The Customs officer was charming, he couldn’t have been more polite. At the same time he couldn’t have been more firm. He was very much afraid that we had got the wrong papers and that the right papers couldn’t be issued there, but could only be issued in Mexico City with the Land Rover. What did he suggest? He gave one of those expressive Latin shrugs, rather like a duck shaking water off its back. The Señor would have to go up to Mexico City and get the appropriate documents before he could release it. He was sorry, he could do no more. We foregathered in a gloomy cluster and reviewed the situation.

‘There’s nothing for it,’ I said. ‘We were going to stay a day in Vera Cruz anyway, so we’re booked in at the hotel. We’ll have to hire a car, go up to Mexico City and get the right papers.’

‘Yes, I suppose so,’ said Jacquie. ‘But what a waste of time and money. I don’t know why the fools at the other end made this mistake over the documents. They knew perfectly well we were only bringing it in for a few months.’

‘There’s no good arguing about it,’ I said. ‘Let’s get our other luggage into store and get installed in the hotel and we can work from there.’

So that is what we did.

As slight compensation for our frustration, the Hotel Mocambo, lying a little way outside Vera Cruz, proved to be so bizarre and enchanting that it took our minds off our troubles for a brief moment. To begin with, it was enormous and had been designed by an architect who, I’m sure, was either deeply influenced by Salvador Dali in his youth or else was a frustrated sea captain, because everywhere there were old sailing-ship wheels. Even the entrance hall itself, which was enormous and circular, had a gigantic one hanging from the ceiling. It must have been about twenty-five feet across. All the windows were barred with wheels of sailing ships. Everywhere there were pictures of ships on the walls. The rest of the edifice – and it can be dignified with no lesser term – was a mass of broad staircases leading hither and yon, open balconies that looked down over the trees to the sea, and great patios with Grecian columns that seemed to have been put up haphazardly with no reason at all. I’m sure any professional architect would have gone mad having spent one night in it, but I found it so extraordinary that I was fascinated by it.

We spent the rest of the day organising a car to take us to Mexico City the following morning, and that evening went down to Vera Cruz in order to sample our first Mexican food. We’d been warned that it was atrocious, so we were more than pleasantly surprised to find that it was anything but. The little Vera Cruz oysters were the sweetest, most delicious oysters I’d ever tasted anywhere in the world, and the great fat prawns, which they split in half and roasted on a flat piece of tin over a fire, were wonderful. They cooked in their own juice and the shells became so crisp that you could eat them as well as the contents of the prawn; it was like eating a sort of strange pink biscuit. Then there were the tortillas, which were new to us, a pancake which you could either have in a rather flaccid condition (which I didn’t care for) or else fried so that they were thin and crisp like biscuits. With them you ate black beans, and a lovely hot sauce made out of green peppers. We gorged ourselves and began to feel brighter in consequence.

The following morning Jacquie, Peggy and I climbed into the car and drove up to Mexico City, leaving Shep and Doreen to enjoy the fleshpots of Vera Cruz. The countryside we travelled through was extraordinary and totally unexpected. One minute we were in the sort of tropical zone that lies round Vera Cruz, where you get pineapples and bananas and various other tropical fruits, and later, as we started to climb, the scenery became totally different; semi-tropical trees and lovely colouring and beautiful shape. Then, quite suddenly, we came to a pine forest zone where the air was cool and we had to put on jerseys. We drove across a great, barren plain and presently could see, looming ahead of us, the volcanoes Popocatepetl, Ixtacihuatl and Ajusco and, huddling at their feet, a great, grey-white cloud.

‘That’s Mexico City,’ said Peggy.

‘What? . . . Do you mean that cloud?’ I asked.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I was told it was like that. That’s smog.’

I looked at her incredulously.

‘Do you mean to say that’s all smog? But they must be suffocating in there.’

‘Well,’ said Peggy ‘they say they have worse smog than anywhere else in the world.’

‘God! It’s going to be pleasant staying there for a couple of days.’

We drove through the outskirts of the city which had a rather tatterdemalion air about them, but once we started getting into the city proper the architecture, although mostly modern, was quite handsome. It was true what Peggy had said about the smog: the smell in the air was almost unbearable; diesel fumes, smoke, petrol fumes, and humanity all mixed up together, so that you felt that your lungs would never be the same again. If you got caught in a traffic jam, which we frequently did, you had the choice of rolling up the windows and roasting to death or trying to breathe once every five minutes in an effort to save yourself from catching lung cancer. How people can live and work in Mexico City I just don’t know. We booked in at a hotel and then, while Jacquie and Peggy went to try to sort out the Land-Rover problems, I seized the opportunity to phone all the contacts I’d been given, to alert them as to our arrival and what we intended to do. I went round to see Mr PeIlam Wright and he was exceedingly kind and helpful and gave me a lot of useful information. He then went with me to see Dr Corzo who is in charge of the conservation of Mexico’s fauna, and his second-in-command Dr Morales. I explained to Dr Corzo what I wanted and he readily agreed to everything, although – in spite of pleading with tears in my eyes – he wouldn’t agree to let me have a permit for the Horned Guan. Apparently they were going to create a special reserve for it and have it properly patrolled so that no poaching could take place. Although I was disappointed that I couldn’t move him on this, at least I felt happy to know that something constructive was being done towards preserving it in the wild state.

The people at the Shell office in Mexico City were extremely helpful to us, and we used their office as a forwarding address for our mail. One day when I went in there the manager, Mr McDonald, happened to catch sight of me as I was inquiring whether there were any letters for us, and called me into his office.

‘Tell me,’ he said, ‘I know you have a party of five, but do you need any extra help at all?’

‘Well, I . . . I might . . .’ I said, cautiously, thinking that perhaps he had a maiden aunt who had adored animals from childhood and felt she would like to join the expedition. ‘Why?’

‘There’s a young man I know,’ he said. ‘He’s a first class chap, knows the country inside out, speaks Spanish, naturally, and he’s also very keen on animals. At the moment he’s waiting to go back to university, but he’s got a couple of months on his hands, and I wondered whether he’d be a suitable person for you to take along. He’s also got his own car, which might help.’

This sounded extremely promising. We needed a second vehicle and we’d been investigating the possibilities of hiring, but the prices were so astronomical that with our dwindling currency we couldn’t afford to indulge in one. If this person had a car of his own it would solve the problem as far as we were concerned.

‘What’s his name?’ I inquired of Mr McDonald.

‘Dix Branch,’ he said. ‘Shall I tell him to come round to the hotel and see you? You needn’t take it any further than that if you don’t want to.’

‘Yes, tell him to come round this evening. Round about five.’

At five o’clock I went down into the foyer of the hotel and found waiting a tall, loose-limbed, well-built young man with long dark hair that had a tendency to fl

op over his forehead, and rather brooding eyes. I liked him instantly although, after five minutes of conversation, I discovered that he took life very seriously, if not too seriously. I explained what we’d come out to do and asked him what sort of car he had. When he said that it was a Mercedes my spirits rose, and on examining it we found that the boot was so enormous it could take practically half our equipment. I said that as far as I was concerned I would be willing to cover his out-of pocket expenses if he’d join the expedition to help us with our work. This he agreed to do. From that moment Dix became invaluable. Not only did he know all the highways and byways of Mexico City, the best places to eat, the best shops to get the various things that we needed, but he also had tireless patience in dealing with officialdom, which was something that we needed badly during the later stages of our trip.

Jacquie and Peggy were having no luck with the Land Rover problem. They were merely being shuffled from office to office and would come back at the end of each day looking thoroughly exhausted and irritable. We had a week of this and then, one day, they came back and found Dix and me sitting in the strange, palm-filled lounge of the hotel, sipping cool drinks. They sank wearily into their chairs.

‘We’ve done it,’ said Jacquie.

‘Marvellous,’ I said. ‘But you don’t look very jubilant about it.’

‘I’m not,’ said Jacquie. ‘You know what it is? Those fools down in Vera Cruz – it’s their mistake. It’s nothing to do with our papers. The Land Rover could have come in straight away. They were looking at the wrong numbers.’

Peggy groaned.

‘Never do I want to see another government office,’ she said.

‘Do you mean to say that we can go and get the Land Rover out?’ I asked.

‘Yes. It’s all fixed,’ said Jacquie. ‘They phoned through to Vera Cruz and gave them a rocket, I’m glad to say. So we can go back tomorrow.’

As we drove back to Vera Cruz the following morning I outlined my plan to Dix: Although I’d been refused permission to capture the Horned Guan and the Quetzal, at least I wanted to see the sort of country that they inhabited. And so I suggested, as a preliminary, once we’d got the Land Rover out and our luggage properly sorted, that we drove straight across Mexico and then down to the Guatemalan border, which was the area in which these birds lived. I thought that this would give us a good overall picture of Mexico and there were many places of interest that we could visit en route. Then, when we’d done this, we would come back to Mexico City, make a base there, and work up the volcano slopes after the Volcano rabbit.

We extracted our Land Rover from the grip of the, by now, suitably servile and apologetic Customs officials, sorted through our luggage in the macabre setting of the Mocambo and left in their custody those items which we thought we would not need. Once we’d done this we were ready and so, at the crack of dawn one morning, we set off to drive right across Mexico to the Pacific coast and then down to the Guatemalan border. I don’t think that anywhere in the world have I travelled through such extraordinarily varied country in such a comparatively short space of time. The first part of our journey took us through the flat lands around Vera Cruz, through sub-tropical creeks and canals where we saw a mass of bird life. There were huge flocks of Boattailed Grackles which flew across the road looking like congregations of small black magpies with short heavy beaks. In the creeks and canals, which were thickly overgrown with water-weed of various sorts, were numerous jacanas or Lilytrotters, those strange little birds with elongated toes that allow them to walk on the water plants lying on the surface of the water. At a casual glance, as they bob their way busily across the water lilies and other plants that grow so thickly in the canals, you could mistake them for moorhens, but as the cars disturbed them they would fly up and you would see their long trailing toes and catch a glimpse of the buttercup-yellow flash of the underside of their wings as they flapped away to safety. We saw numbers of Boat-billed herons which I think must be the most lugubrious of all the water birds; with their squat, boat-shaped beak and large sorrowful eyes they sat in clusters in the trees, their strange beaks tucked into their chests, looking like depressed conventions of Donald Ducks.

We passed through villages and towns which were a shimmering blue haze of jacaranda trees and the houses themselves seemed almost weighed down under the great shawls of bougainvillaea – purple, pink, orange, yellow and white. Then, as the road climbed a little higher, we passed through almost tropical forest where the branches of the trees sprouted great waterfalls of greeny-grey Spanish moss, and the trunks of the trees were sometimes almost completely obscured by orchids and other epiphytes that grew on them. Here the steep banks of the road were covered with a tapestry of smaller plants and shrubs and, in particular, great masses of enormous ferns. The plant life was so varied and extraordinary that I cursed myself for not knowing more about botany.

It was while we were travelling through this magnificent country that it began to rain – and rain as it can only rain in the tropics. Great gouts of water plummeted down from the sky so that the road, which was an earth one, was immediately turned into a dangerous mire, and visibility cut down to a few inches. Jacquie, Doreen and Shep were travelling in the Land Rover, and Peggy and I and Dix were in his Mercedes leading the way. We kept the Land Rover behind us so that, should the Mercedes – for some reason or other – get into trouble, the Land Rover could always pull her out. As visibility was cut down to nil by this grey sheet of water that was pouring from the skies, I enlivened the time by reading some extracts from an enchanting guide book that I had been fortunate enough to come across in Mexico City.

‘We’re not touching in at Acapulco, are we?’ I inquired of Dix, for my knowledge of the geography of Mexico was still slightly hazy.

‘No,’ said Dix, morosely, ‘and I wouldn’t advise you to go there anyway. It’s just a playground.’

‘Well, according to this book, it sounds fascinating. Listen to this: “Its particular topography offers impressive panoramas: Quiet and crystalline bays and inlets; beaches worthy of seeing due to the huge waves; the water is warm as well as the climate with soft winds almost the year round (77°F) which makes the clothes to wear must be light. It is rare the Sun does not shine, as usually it rains by night. The natives have kept their old customs, specially in dressing.”’

‘Wonderful,’ said Peggy. ‘What a pity we’re not going there.’

At this point we had a puncture and Dix and I had to get out and change the wheel, although Dix did most of the work. We got back into the car, dripping wet, and continued at our snail’s pace down the road through the torrential rains. When I had mopped the water off my face and hair and hands, I turned once again to my guide book.

‘Now here’s the place we ought to go to,’ I said. ‘Just listen: “Due to its temperate climate, its clear sky and shining sun almost all over the year, this place can be considered as ideal for relaxing. The hospitality and friendliness of the inhabitants make the visitor to feel at home, the peaceness of this town is a real soothing for those who are looking for a place to relax their broken nerves because of the excitement of the present way of life almost everywhere. Its Parish and picturesque main square must be visited, as well as its market.”’

Presently the rain stopped and soon afterwards we came to the end of this tropical forest and, in the extraordinary way that vegetation grows in Mexico, passed straight out of tropical forest into pine forest at high altitude. As the sky cleared we drew up to have some coffee that Jacquie had thoughtfully provided. Whereas, some ten minutes previously, we had been sweating gently in the tropical heat, we now found the air so crisp and cold that we were forced to put on all the warm clothing we could find.

Now the road went mad and wriggled its way down into valleys and up precipitous mountainsides and around and along them. The vegetation grew more and more extraordinary as we went along. In the valleys there would

be the lushness of the tropics and then a few minutes of climbing up a winding road along a hillside and you would come to a great area in blazing hot sunshine, dry and desiccated, covered with rank after rank of trees that were completely devoid of leaves and whose trunks were of the most beautiful silky-red colour. Both trunks and branches were so twisted that it looked, for mile after mile, as though you were passing through an enormous frozen corps de ballet. And then you would round a corner and suddenly there was not a red tree to be seen, but in their place were similar ones, only with a silver-grey bark that gave off an almost metallic gleam where the sun hit it. Again, these were completely leafless.

Round yet another corner and the trees had all disappeared and in their place were gigantic cacti, some of them about twenty feet high. They were the candelabra variety, which meant that they have curving arms sticking out from the main stem so that they look like extraordinary green candlesticks growing thickly all over the mountainside. Here, unidentifiable hawks wheeled in slow circles in the blue sky like little black crosses, and frequently across the road would gallop a Road-runner – a strange little bird with a crest and a long tail and enormous flat feet. When they ran, their feet almost touched their chins, and they leant forward with the earnest air of somebody trying to break the record for the mile. The bird life and the super-abundance of vegetable life made me wish that we could stop more often on the road, but I knew that this would be fatal, for our time in Mexico was short, dictated by the amount of currency reluctantly allowed us by the Bank of England. It was a race against time.

Presently we came to a small town called Tule. To my surprise Dix parked the car carefully alongside the railings of what looked like a little park with a church in it. The Land Rover drew in immediately behind us.

‘What are we stopping here for?’ I inquired.

A Zoo in My Luggage

A Zoo in My Luggage The New Noah

The New Noah The Bafut Beagles

The Bafut Beagles Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Catch Me a Colobus

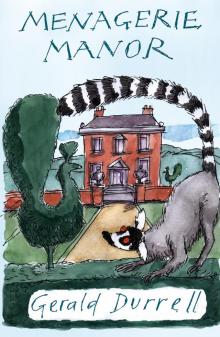

Catch Me a Colobus Menagerie Manor

Menagerie Manor The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Ark on the Move

Ark on the Move My Family and Other Animals

My Family and Other Animals Two in the Bush (Bello)

Two in the Bush (Bello) The Stationary Ark

The Stationary Ark The Whispering Land

The Whispering Land Three Singles to Adventure

Three Singles to Adventure Fillets of Plaice

Fillets of Plaice The Aye-Aye and I

The Aye-Aye and I Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons

Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons The Drunken Forest

The Drunken Forest Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories

Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy)

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) The Corfu Trilogy

The Corfu Trilogy Marrying Off Mother

Marrying Off Mother Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush