- Home

- Gerald Durrell

The Drunken Forest Page 2

The Drunken Forest Read online

Page 2

‘Hullo, Gerry! You up?’ he said, faintly surprised, and sucked vigorously at the little pipe, which responded with a musical gurgle like a miniature bath emptying.

‘What are you doing?’ I asked austerely.

‘Having my morning mate,’ he answered, giving another liquid gurgle on the pipe. ‘Like to try it?’

‘Isn’t that the herb tea?’ I inquired.

‘Yes. Drink it out here as frequently, if not more frequently, than tea in England. Try some; you might like it,’ he suggested, and handed me the little silver pot and pipe.

I sniffed suspiciously at the dark brown liquid with its crust of floating herbage. The scent was rich and pleasant, like a hayfield under a hot sun. I put my lips to the little pipe and sucked. There was a fruity wheeze, and a stream of boiling liquid gushed into my mouth and scalded my tongue. Wiping my streaming eyes, I handed the pot back to Ian.

’Thanks,’ I said. ‘I’ve no doubt it’s an acquired taste to drink it at that temperature, but I’m afraid my taste-buds wouldn’t stand it.’

‘Well, you can drink it cooler than this,’ said Ian doubtfully, ‘but I think it loses its flavour.’

Later I tried drinking mate at a more humane temperature, and I found it pleasantly soothing, with its aroma of new-mown hay and faintly bitter, astringent taste that was quite refreshing. But I could never cultivate the ability to drink it at the heat of molten metal, as I presume a connoisseur would like it.

We meandered through an excellent breakfast, and then wandered out into the brilliant day to examine the surrounding countryside. Hardly had we left the copse of eucalyptus that ringed the estancia like a giant fence, when we came upon a tree-stump in the long grass, and perched on top of it was an oven-bird’s nest. I was amazed, when I examined it closely, that a bird of this size could produce such a large and complicated structure. The nest was globe-shaped, roughly twice the size of a football, strongly made of mud combined with roots and fibres, so that it formed a sort of avian reinforced concrete. Looked at from the front, where there was an arched entrance, the whole thing resembled a miniature version of an old-fashioned bread-oven. I was interested to see what the inside of the nest was like, so, being assured by Ian that it was an old one, I prised it off the tree-stump and cut carefully through the brick-like top of the dome with a sharp knife. When the top was removed, the whole thing looked like the inside of a snail shell: a passage-way ran in to the left for some six inches from the arched door, following the curve of the outside wall, but bent in at the right of the door so as to form the passage-way. Where the passage ended, the natural shape of the nest formed a circular room, which was neatly lined with grass and a few feathers. While the outside of the whole structure was rough and uneven, the inside of the little room and the passage-way was smooth and almost polished. The more I examined the nest, the more astonished I became that a bird, using only its beak as a tool, could have achieved such a building triumph. No wonder the people of Argentina look with affection upon this sprightly bird that paces so pompously about their gardens and makes the air shiver with its cheerful, ringing cries. Hudson relates a charming story about a pair which had built a nest on the roof of a ranch-house. One day the female unfortunately got caught in a rat trap, which broke both her legs. Struggling free, she managed to fly up into her nest, and there eventually died. Her mate flew about for several days, calling incessantly, and finally disappeared. Within two days he was back again, accompanied by another hen. The two birds promptly set to work and plastered up the entrance of the old nest, containing the first wife’s remains. This done, they constructed a second nest on top of this crypt, and here they successfully reared their brood.

Certainly, as birds go, the oven-bird appears to have more than his fair share of personality and charm, for he has a strange power over even the most hardened cynics. Later on during our stay an elderly peon, who had no sentimentality in his make-up and suffered no qualms at killing anything from men to insects, solemnly told me that he would never harm an hornero. Once, he said, when out riding in the pampa, he came upon an oven-bird’s nest on a stump. The nest was half completed and the mud still damp. Dangling from one side of it was the owner, caught round the feet by a long thread of grass it had obviously been using as reinforcement. The bird must have been hanging there for some time, fluttering vainly in an attempt to free itself, and it was nearly exhausted. Moved by a sudden impulse, the peon rode up to the nest, took out his knife and carefully cut away the entangling grass and placed the exhausted bird carefully on top of its nest to recover. Then an extraordinary thing happened.

‘I swear that this is true, señor,’ said the peon. ‘There was I, not more than a couple of feet away from the bird, and yet it showed no fear. Weak as it was, it struggled to its feet, and then put its beak up and started to sing. For nearly two minutes it sang to me, señor – a beautiful song – and I sat on my horse listening. Then it flew off across the grass. That bird was thanking me for saving its life. A bird that can show gratitude in that manner, señor, deserves respect from a man.’

A hundred yards or so from the oven-bird’s nest, Jacquie, who was some distance away to my right, started to make inarticulate crooning noises and to beckon me frantically. Joining her I found she was gazing rapturously at the mouth of a small burrow, half hidden among the grass tussocks. At the mouth of the burrow squatted a small owl, stiff as a guardsman, watching us with round eyes. Suddenly he bowed up and down two or three times, very rapidly, and then froze once more into his military stance. This was such a ludicrous performance that both Jacquie and I giggled, and the owl, after giving us a withering glare, launched himself on silent wings and glided away across the wind-rippled grass.

‘We must catch some of those,’ said Jacquie firmly. ‘I think they’re delightful.’

I agreed, for owls of any sort have always appealed to me, and I have never been able to make any collection without a sprinkling of these attractive birds finding their way into it. I turned towards where Ian was pacing through the grass, like a solitary and depressed-looking crane.

‘Ian,’ I shouted, ‘come over here. I think we’ve found a burrowing owl’s nest.’

He came loping over, and together we examined the entrance of the hole where the owl had been sitting. There was a patch of bare earth from the excavations, and this was liberally sprinkled with the gleaming chitinous shells of various beetles and round castings composed of tiny bones, fluff and feathers. It certainly looked as though the burrow was used for more than just roosting in. Ian gazed down, pulling his nose reflectively.

‘D’you think there’s anything in there?’ I asked.

‘Hard to say, he replied. ‘It’s the right season, of course – in fact the youngsters should be fully fledged by now. Trouble is these owls make several burrows, and they only use one for nesting in. The peons say that the male uses the others as sort of bachelor apartments, but I don’t know. It means we may have to dig out any number of these holes before we strike lucky; but, if you don’t mind a good many disappointments, we can have a try.’

‘You can disappoint me as much as you like, as long as we get some owls in the end,’ I said firmly.

‘Right. Well, we’ll need spades, and a stick of some sort to see which way the tunnels lie.’

So we retraced our steps to the estancia, and there Mrs Boote, delighted that we were hot on the trail of specimens so soon after our arrival, unearthed a fascinating array of gardening tools, and told a peon to stop whatever he was doing and to go with us in case we needed help. As we trailed across the garden, looking like a gravedigger’s convention, we stumbled upon Dormouse Boote, slumbering peacefully on a rug. She awoke as we passed and asked sleepily where we were off to. On being informed that we were off to capture burrowing owls, her blue eyes opened wide and she suggested that she should drive us out in the car to the owl’s nest.

�

�But you can’t drive the car across the pampa . . . it’s not a jeep,’ I protested.

‘And your father’s just had the springs renewed,’ Ian reminded her. She gave us a ravishing smile.

‘I’ll drive very slowly,’ she promised, and then, seeing that we were still doubtful, she cunningly added, ‘and think how much more ground you’ll be able to cover in a car.’

So we lurched out across the pampa to the first owl-hole, the springs of the car twanging melodiously, and causing everyone except Dormouse twinges of conscience.

The hole we had found turned out to be some eight feet in length, curving slightly like the letter ‘C’, and about two feet at the greatest depths below the surface. We discovered all this by probing gently with a long and slender bamboo. Having marked out with sticks a rough plan of how the burrow lay, we proceeded to dig down, sinking a shaft into the tunnel at intervals of about two feet. Then each section of tunnel between the shafts was carefully searched to make sure nothing was hiding in it, and blocked off with clods of earth. At length we came to the final shaft, which, if our primitive reckoning was correct, should lead us down into the nesting chamber. We worked in excited silence, gently chipping away the hard-baked soil.

At intervals during our excavations we had pressed our ears to the turf, but there had been no sound from inside, and I was half convinced that the burrow would prove empty. Then the last crust of earth gave way, and cascaded into the nesting chamber, and glaring up out of the gloomy hole were two little ash-grey faces, with great dandelion-golden eyes. We all gave a whoop of triumph, and the owls blinked very rapidly and clicked their beaks like castanets. They looked so fluffy and adorable that I completely forgot all about owls’ habits, and reached into the ruins of the nest-chamber and tried to pick one up. Immediately they transformed themselves from bewildered bundles consisting of soft plumage and great eyes, to swollen, belligerent furies. Puffing out the feathers on their backs, so that they looked twice their real size, they opened their wings on each side of their bodies like feathered shields, and, with clutching talons and snapping beaks, swooped at my hand, I sat back and sucked my bloodstained fingers.

‘Have we got a thick cloth of some sort?’ I asked – ‘something thicker than a handkerchief, with which to handle these innocent little dears?’

Dormouse sped off to the car and returned with an ancient and oil-stained towel. I doubled this over my hand and made a fresh attempt. This time I succeeded in grabbing one of the babies round the body, and although the towel kept off the attacks of his beak, I was still pricked by his clutching talons. Having got a good grip on the towel, he then refused to let go, and it took some time to disentangle his feet and pop him into a bag. His brother, now facing the enemy alone, seemed to lose a lot of his nerve, and he was much less trouble to catch and put in a bag. Hot, earth-stained, but feeling very pleased with ourselves, we reentered the car. For the rest of the day we zigzagged across the pampa, waiting for pairs of burrowing owls to fly out of the grass. Then we would wander about the spot until we had located the hole and proceed to dig it out. We met with more disappointments than successes, as Ian had predicted we would, but at the end of the day (having dug up what appeared to be several miles of tunnel), we returned to the estancia with a very satisfying bag of eight baby burrowing owls, who promptly proceeded to consume meat and beetles in such vast quantities that we began to wonder if their harassed parents would really miss them, or whether they would look upon the capture of their offspring as a merciful release.

Having now got our first specimens from Los Ingleses, others followed rapidly. The day after the capture of the burrowing owls, a peon came to the house holding a box which contained two fledgling guira cuckoos. These birds are quite common in Argentina, and even more so in Paraguay. In shape and size they look like an English starling, but there the resemblance ends, for guira cuckoos are clad in pale fawny-cream plumage, streaked with greenish black, with a tattered gingery crest on the head, and long, magpie-like tails. They travel together through the bushes and woods in little companies of between ten and twenty, and they look very handsome as they glide from bush to bush en masse, like flights of brown-paper darts. Apart from admiring these flocks of cuckoos in flight, I had not really given the species any serious thought, until we received these two babies. I discovered immediately I undid the box in which they were confined that guira cuckoos are not like other birds at all. To begin with, I am convinced that they are mentally defective from the moment of hatching, and nothing will make me alter my opinion. As I lifted the lid from the box, it disclosed the two guiras squatting straddle-legged in the bottom of the box, long tails spread out, and ginger crests erect. They surveyed me calmly with pale yellow eyes that had a glazed, dreamy, far-away expression in them, as though they were listening to distant and heavenly music too faint for mere mammals like myself to hear. Then, like a perfectly trained harmony team, they raised their uneven crests still farther, opened their yellow beaks and let forth a loud, hysterical series of sounds like a machine-gun. This done, they lowered their crests and flew heavily out of the box, one landing on my wrist and one on my head. The one on my wrist uttered a pleased, chuckling sound and sidled up to the buttons on my coat sleeve, which he proceeded to attack with raised crest and every symptom of ferocity.

The one on my head grasped a large quantity of hair in his beak, straddled his legs and proceeded to pull at it with all his might.

‘How long has this man had them?’ I asked Ian, astonished at the birds’ impudence and tameness.

Ian and the peon had a rapid exchange of Spanish, and then Ian turned to me.

‘He says he caught them half an hour ago,’ said Ian.

‘But that’s impossible,’ I protested; ‘these birds are tame. They must be someone’s pets who’ve escaped.’

‘Oh, no,’ said Ian; ‘guiras are always like that.’

‘What, as tame as this?’

‘Yes. They seem to have no fear at all when they’re young. They’re not quite so silly when they are adult, but almost.’

The one on my head, discovering that the idea of scalping me was impossible, now descended to my shoulder and tried to see how much of his beak would fit into my ear without getting stuck. I removed him hurriedly and placed him on my wrist with his brother. They both immediately carried on as though they had not seen each other for years, raising their crests, gazing lovingly into each other’s eyes, and trilling with the speed of a couple of road drills. When I opened the door of a cage and placed my wrist near it, both birds hopped inside and up on to the perch as if they had been born in captivity. Intrigued by this display of avian nonchalance, I went in search of Jacquie.

‘Come and see the new arrivals,’ I said, when I found her, ‘the answer to a collector’s dream.’

‘What are they?’

‘A pair of those guira cuckoos.’

‘Oh, you mean those gingery things,’ she said disparagingly. ‘I don’t call them very exciting.’

‘Well, come and see them,’ I urged; ‘they’re certainly the weirdest pair of birds I’ve come across.’

The cuckoos were sitting on the perch, preening themselves. They paused briefly in their toilet to fix us with a glittering eye and rattle a brief greeting before continuing.

‘They’re a bit more attractive when you see them close to,’ Jacquie admitted; ‘but I don’t see what you’re making a fuss about.’

‘Don’t you notice anything about them . . . anything unusual?’

‘No,’ she said, surveying them critically. ‘It’s a good thing they’re tame. Saves a lot of trouble.’

‘But they’re not tame,’ I said triumphantly; ‘they were only caught half an hour ago.’

‘Nonsense!’ said Jacquie firmly. ‘Why, just look at them. You can see they’re quite used to being in a cage.’

‘No, they’re not. Acc

ording to Ian, at this age they’re quite stupid, and they’re very easy to catch, and as tame as anything. When they get older they develop a little more sense, but apparently not very much.’

‘I must say they are rather peculiar-looking birds,’ said Jacquie, peering at them closely.

‘They look mentally defective to me,’ I said.

A Zoo in My Luggage

A Zoo in My Luggage The New Noah

The New Noah The Bafut Beagles

The Bafut Beagles Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Catch Me a Colobus

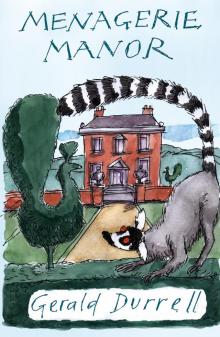

Catch Me a Colobus Menagerie Manor

Menagerie Manor The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Ark on the Move

Ark on the Move My Family and Other Animals

My Family and Other Animals Two in the Bush (Bello)

Two in the Bush (Bello) The Stationary Ark

The Stationary Ark The Whispering Land

The Whispering Land Three Singles to Adventure

Three Singles to Adventure Fillets of Plaice

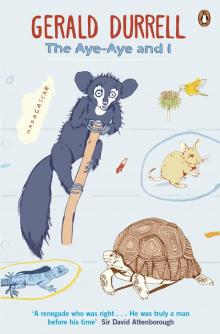

Fillets of Plaice The Aye-Aye and I

The Aye-Aye and I Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons

Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons The Drunken Forest

The Drunken Forest Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories

Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy)

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) The Corfu Trilogy

The Corfu Trilogy Marrying Off Mother

Marrying Off Mother Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush