- Home

- Gerald Durrell

The Aye-Aye and I Page 2

The Aye-Aye and I Read online

Page 2

‘What are the roads like from point A to point B?’ we inquired.

‘Mon Dieu! Don’t even attempt it!’ our informant cried, recoiling in horror at the thought. ‘Potholes the size of wine casks and in places the road completely disappears.’

From other well-wishers, we garnered the knowledge that this same road was as smooth as silk, as rough as a crocodile’s back, or just like the Rue de Rivoli, only better.

‘What about the ferries?’ we inquired hopefully.

‘The ferries, you ask? Ma foi, they are never on time and if the tide is wrong you may be held up for twenty-four hours or worse.’

‘The ferries? Don’t worry, they are excellent, always on time.’

And so it goes on: take rice, don’t take rice; take oil, don’t take oil; take tinned stuff, don’t bother to take tinned stuff. The town of Anamatarateviolala – a name which trips lightly off the tongue – through which we thought we might pass, is described in such glowing terms that we expect to find branches of both Harrods and Fortnum’s there. But another confidant will tell you that the town is a gastronomic desert.

‘Ask for Pierre,’ we were advised. ‘He is a mine of information.’ And where do we find him? ‘Oh, just stop and ask anyone in the street. They all know Pierre, he’s the best-known person there. He can fix anything. He could find you a dinosaur on top of the Eiffel Tower, or a deep-freeze at the North Pole.’ You begin to long to meet this miracle worker, to lay your head on his honest breast and have all your problems solved. Of course, when you get to Anamatarateviolala you find neither Harrods nor Fortnum’s, nor can you find anyone who knows Pierre.

All this takes place in the bar of the Hotel Colbert where several tables have been cobbled together to accommodate your eager well-wishers. The tables are a forest of beer and Coke bottles and the pile of drink tabs is so thick it looks like the proofs of the Gutenberg Bible. In between the bottles are maps, information packs, and frantic notes which later will require a Scotland Yard graphologist to decipher. In front of us passes a kaleidoscope of faces, white, café au lait, chocolate, or yellow as chamois leather.

When, finally, we go to bed exhausted, the mosquitoes descend on us, each adding its own piping voice to the insect Mozart opera. The bathwater is dark brown and smells of vanilla. Early morning tea is served by a gentle Malagasy and it is also dark brown and smells of vanilla. I wonder vaguely, as another day dawns, whether they simply fill the teapot from the hot tap in the kitchen. However, an early breakfast of mango, pineapple, lychees and fresh strawberry juice revitalises the tissues.

In order to avoid the host of informants who are eagerly awaiting our arrival in the bar, we find a back way out of the hotel and go to refresh our spirits by paying a visit to the zoma, one of the most fascinating markets in the world.

Here, under the innumerable white umbrellas which, from a distance, make the market look like a field of mushrooms, lies the provender of the city. There were pyramids of pulses, red, green and fawn; twisted bundles of herbs in every shade of green and with strange leaf shapes, looking like fodder enough for a sorceress’s stallion; piles of lettuce and watercress, dripping water and gleaming as if newly varnished; a host of powdered spices, like the palette of some Malagasy Titian or Rembrandt, raw umber, rose madder, greens, blues, smouldering reds, and yellows as delicate as a crocus bud, all of them waiting to be mixed with oil so that they could release their many fragrances upon the tongue; bags of beans of bewildering shapes and colours, some round, some like bricks, some as minute as pin heads with what appeared to be neat little black zip fasteners down one side. Next to them were woody chunks of liquorice and vanilla pods, all sharp and tangy to the nose; nearby, pyramids of jade-green duck eggs; and alongside these were similar piles of chickens’ eggs, white as chalk or brown as toast. Beneath these domes were the chickens, their legs tied together, lying in untidy, indignant bundles like animated feather dusters, and ducks honking gently as they nervously watched the passing forest of brown legs.

Turning from this spectacle we were confronted by huge bowls of tiny fish, glittering like silver coins, and larger ones – black as coal – laid in rows. Next to them lay a panoply of great carp, pouting sulkily side by side, each large scale rimmed with silver or gold so the carp looked as if they were wearing chain mail. Beside them were the meat stalls, the last resting place of the strange, humped zebu cattle, gory carcasses pulsating in a shroud of flies. Nearby was a bowl of skinned and cooked zebu lips, transparent, gelatinous, quivering like dirty frog spawn, with the occasional hair attached. Over the bowl crouched an ancient woman with a face like a walnut, dressed in rags, stuffing these awful slabs into her toothless mouth with the aid of a tin fork. But not far from her could be found stalls covered with beautifully embroidered tablecloths and dresses, and vast quantities of brilliant fresh flowers. It was like finding a rainbow in a mortuary. Next to these, tottered piles of raffia baskets like brandy snaps, looking good enough to eat.

Invigorated by the sights and scents and sounds of the zoma we made our way back to our hotel room for a conference of war, carefully avoiding the bar full of eager informants bubbling with misinformation.

There were four of us: my wife Lee; myself; lanky, unflappable John Hartley, my PA of many years’ standing; and Quentin Bloxam our curator of reptiles – tall, muscular, with a determined-looking face that suggested ‘Bulldog’ Drummond on the way to rescue his wife Phyllis from the clutches of the unspeakable cad Carl Peterson. We sat drinking beer and discussing the modus operandi of the trip. We had to go to three places: the Mananara region in the east, where we hoped to catch the elusive aye-aye, the forests near Morondava in the west, where the flat-tailed tortoise and the giant jumping rat had their respective abodes, and Lac Alaotra, where the gentle lemur, diminutive and shy, lurked furtively in the reed beds.

We eventually decided to split our forces in order to save time. John and Quentin would take our two Toyota Land Cruisers (one donated by our sister organization, Wildlife Preservation Trust International, one donated by the munificent Toyota company) to Morondava and set up camp there. Meanwhile Lee and I would go north-east to Lac Alaotra and try to find gentle lemurs. If successful, we would bring them back and board them at the Tsimbazaza Zoo in Antananarivo and then fly to join the others in Morondava. This seemed to us all an excellent campaign plan and, cheered by our decision, we went downstairs and had a couple of dozen small, sweet and succulent Malagasy oysters for lunch to celebrate.

To assist us in our plans for Lac Alaotra, we had enlisted the aid of Olivier Langrand (who had just published a much-needed guidebook to the birds of Madagascar) and his beautiful and formidably capable wife, Lucienne. She had done a lot of work on the lake trying to track down two species of bird (a pochard and a grebe), both endemic to the lake and believed to be extinct. Lucienne told us that it was not possible to work around the lake without Mihanta. My heart sank. Was this going to be another of those elusive Pierres who vanished from sight when you appeared? But no, I had misjudged Lucienne, for the next morning she appeared, exuding charm and efficiency in equal quantities, and in tow was a charming Malagasy with a wide, happy smile and humorous eyes. He was a fourth-year medical student who had been born in one of the numerous villages that surround Alaotra and therefore had a sprinkling of cousins, uncles, aunts, nephews and nieces in nearly every community. He immediately and deftly took control of our whole enterprise. We were to fly up to the lake and come back by train with any animals we obtained. However, he would go ahead by train, taking our animal cages with him, arrange a room in a hotely (all restaurants are called by the name hotely. As many of them also have accommodation – of a sort – for the weary traveller, I took to calling both restaurants and hotels hotelys, much to Lee’s annoyance, for she is a stickler about these things. But I stuck to my argument that hotely was a far more enchanting name than any other for such hostelries.) and organize transport for us to go and search the villages around the lake for any gentle

lemur (Hapalemur griseus alaotrensis) kept in captivity. He explained that this was a good time of the year to get lemurs as it was in this season that the local people burnt large patches of the reed beds to make room for more rice paddies. An added advantage was that the lemurs driven out by the flames could be clubbed to death and sold as food or captured and sold as pets. Needless to say, all of this is strictly against the law but continues unabated, nevertheless.

The tale of Lac Alaotra is a dismal one and it is, I am afraid, the sort of thing that is happening throughout Madagascar. To begin with, the lake – the biggest on the island – was Madagascar’s rice bowl and met all of the country’s considerable needs. (The Malagasy consume more rice per capita than any other people.) The lake is surrounded by a picture frame of gentle hills, once covered in forests. However, over the years, these natural bastions that protected the lake were felled for farmland. Thus the forest shield was removed and what was grown on the exposed soil only lasted a few years, after which the hills gradually started to disintegrate. With no trees to hold it in place, the degraded soil made its way down into Alaotra like a red glacier, slowly silting and clogging the waters, slowly making the lake vanish. Now, the lake is no longer the rice bowl of Madagascar and the country has to import this staple food, paying out foreign currency from a feeble economy.

You cannot blame the Malagasy people, but rather the people who have ruled in the past. To the peasant, the felling of a piece of forest is not looked upon as ecological suicide, but as a way of gaining a bit of soil that will give him a crop for a few years, while the forest he fells forms fuel for the fires that feed him. His forefathers did it, why should not he? He does not know that there are five times as many of him as there were in his grandfather’s time and that this profligate use of nature’s bounty will starve his grandchildren.

Our flight to Ambatondrazaka, the largest town on the shores of Lac Alaotra, was depressing beyond belief. Miles and miles of hill country, once forested, now showed bald and split with a million scarlet wrinkles, the first signs of erosion, the disintegration of the land. The flight lasted three quarters of an hour and beneath us we saw nothing but this horrifying landscape. I said to Lee, ‘It’s like flying over the Sahara,’ to which she replied, ‘This is how the Sahara came into being.’

We landed on a grass airstrip and the aircraft taxied round until it was outside the small building that appeared to be control tower, bar and luggage carousel, none of which at the moment were in use. There was no sign of a welcoming Mihanta and again I wondered if he was mythical. We hoiked our luggage outside the air terminal (if you could call it that) and gazed down a long, red-mud road, full of potholes and gleaming puddles, for there had obviously been a considerable downpour in the night. The road disappeared into a haze of trees, but nowhere could we see a sign of Mihanta. There was one elderly taxi, into which a very large Malagasy lady, her equally large daughter and a child were being installed.

‘Let’s get into the centre of town and send out search parties from there,’ I said to Lee. ‘Let’s ask them for a lift.’

With kindly eyes and broad smiles they welcomed us into the cab. There was just enough room. We set off down the road, the car springs squeaking protestations at every pothole, the water from the puddles squirting like blood from under our wheels. We had progressed, as on a trampoline, for a quarter of a mile, learning in the course of it all the intimate details of the large lady’s private life, when another car approached containing a gesticulating Mihanta. So, in a broken, red looking-glass of puddles, we exchanged cars and compliments, and Mihanta, full of apologies, drove us to our hotely.

By Malagasy standards, this was a substantial building, run by a Chinese man and his Malagasy wife and wonderfully situated on the opposite side of the road to the open-air market of Ambatondrazaka. I found this fascinating but most distracting. When sitting downstairs in the bar-lounge-restaurant three windows looked out onto the street and the market went on from dawn to dusk.

I noticed immediately that all the women wore hats. Now, I love women in hats, so I was bewitched. Elegant Malagasy ladies would glide past the window, wrapped in multicoloured cloth lambas (in which they carried their babies strapped to their backs), peering at you from under the broad brim of beautifully woven straw hats. Of course, the younger ones did not yet have babies. They slid along, their lambas wrapped around them to display every provocative curve and, from under their broad-brimmed headgear, they would gaze out with eyes the size of black mulberries. It was an enchanting sight but not, strictly speaking, what I had come for.

Our room was large, full of unnecessary furniture and a bed that must have been designed for St Augustine, to discourage both sex and sleep. Its windows were barred, which gave it a vague flavour of Alcatraz. However, by Malagasy standards it would be rated three stars in the Michelin guide.

The moment we arrived I was smitten with a tummy upset, such as one is prone to in the tropics. It can either be mild or devastating and painful. In my case it was the latter. Taking vast quantities of medication, I hoped for the best, since Mihanta had informed us that the first thing we had to do was to make ourselves known to the two local presidents – one on each side of the lake – in whose territories we would be operating.

He had engaged a large, handsome Malagasy with the unlikely name of Romulus, who would drive us hither and yon in his battered car, which looked as though it had been salvaged from a junkyard. All the windows were wound down and there were no handles to wind them up. One of the back doors was jammed, both windscreen wipers had disappeared, the front and back of the vehicle had been in close contact at one time or another with a brick wall, the tyres were as bald as vultures and the exhaust pipe drooped behind, making an untuneful scraping noise as we progressed. However, the engine worked, after a fashion, with much wheezing and grunting and occasional gasps and stoppages.

In this decrepit vehicle we made our way to the outskirts of the town to meet the first president. He was a highly intelligent, energetic man and the moment we shook hands with him we realised why he had reached his position. Lee carefully explained our mission to him and he was obviously impressed, not only by Lee’s command of French but by her personality. He glanced at me in a friendly fashion once or twice, but for the rest of the time his eyes were riveted on her and he finally said that he would do anything we wanted. I felt that, if asked, he would happily have presented Lac Alaotra to Lee as a gift. We left him in a flurry of good wishes and then drove off to the western shores of the lake to meet the second president.

The drive was depressing. The undulating hills that surrounded the lake were denuded and the flat areas that had once been water and fertile rice paddies were now silted up and sterile. On the scattered weeds that now grew there a few zebu herds and some flocks of geese grazed in a desultory fashion. It was a desolate sight. In the extreme distance we could glimpse the lake and the reed beds, where the lemurs we had come to search for had their ever-diminishing home.

The village of Amparafaravolo was large and fairly prosperous-looking: mud houses thatched with reed and brick-built public buildings. In one of these we were shown into the president’s anteroom. Unfortunately, he had been kept at a meeting and could not see us but, we were told, his deputy would see us at two-thirty. By now, the soothing effects of the antibiotics I had taken had worn off. I felt as if I had a very boisterous crocodile embedded in my stomach and the need to be in close proximity to a lavatory became mandatory. So we went to the local hotely and had an uninteresting but adequate lunch.

On the stroke of half-past two we were ushered into the deputy’s office. A tall, slender Malagasy with frosty white hair, he was dressed in an impeccable white linen suit, and a gay red and yellow foulard tied round his neck like a bouquet of orchids. The crease on his pants would have brought a flush of delight to M. Guillotine. He listened politely to Lee’s description of our quest, but it was obvious that he was more interested in himself than in anything else. He

was a bureaucrat who had made it. As Lee talked, outside the window an aggressive cockerel with a harsh crow was telling all the world that this was his territory, and next door someone was attempting to play ‘Silent Night’ on a piano-accordion and coming to grief on the second verse. Our friend in the white suit said he would be delighted to write us a letter which, he implied, would open all doors for us. He then called on his secretary and, while she sat there patiently, he wrote out the letter in longhand and then handed it to her to be typed. She took it away and we could hear her starting to type as if she had only one finger.

By this time, my stomach cramps were extremely painful and the need for a lavatory was paramount. Since it appeared that the letter was going to take as long to procure as the Domesday Book, I requested to be shown the way to what the Americans euphemistically call a ‘comfort station’. I was led out to the back of the building – where the harsh-voiced cockerel viewed me with disdain – and then shown towards a breeze-block building approximately the size of a small cupboard. On entering this, I decided immediately that it was the sort of facility even a Greek taverna owner would consider unhygienic. There were two cement footsteps and a hole in the ground. It was the ominous, omnivorous, sibilant rustling noises emanating from this hole that made me realise I was sharing this odoriferous boudoir with twelve million maggots. As well as these companions the place was home to some of the biggest cockroaches I have ever been introduced to. They were considerably longer than my thumb, chocolate and bronze, sliding about silently and gleaming like newly minted Rolls-Royces. Outside, the person with the piano accordion was still trying to master ‘Silent Night’ and the aggressive cockerel was accompanying him. Neither could get to grips with the second verse.

I went back to the deputy’s office and, finally, the letter was produced. The deputy signed it with a flourish and we all stood up to leave, but then his bureaucratic eye detected a flaw in the document. Our name had been spelt with only one ‘r’. So the letter was given back to the abashed and berated secretary to be retyped and we all sat down again. After what seemed like a century, during which the piano-accordion player made no musical progress, the new letter was produced, perused for error, finally signed, and we took our leave. This whole business had taken up an hour and a half of our time and we never had any reason to use the letter.

A Zoo in My Luggage

A Zoo in My Luggage The New Noah

The New Noah The Bafut Beagles

The Bafut Beagles Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Catch Me a Colobus

Catch Me a Colobus Menagerie Manor

Menagerie Manor The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Ark on the Move

Ark on the Move My Family and Other Animals

My Family and Other Animals Two in the Bush (Bello)

Two in the Bush (Bello) The Stationary Ark

The Stationary Ark The Whispering Land

The Whispering Land Three Singles to Adventure

Three Singles to Adventure Fillets of Plaice

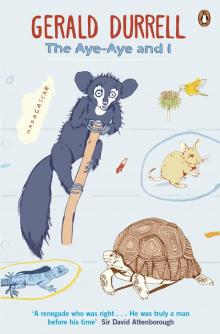

Fillets of Plaice The Aye-Aye and I

The Aye-Aye and I Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons

Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons The Drunken Forest

The Drunken Forest Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories

Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy)

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) The Corfu Trilogy

The Corfu Trilogy Marrying Off Mother

Marrying Off Mother Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush