- Home

- Gerald Durrell

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) Page 3

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) Read online

Page 3

That he knew everyone on the island, and that they all knew him, we soon discovered was no idle boast. Wherever his car stopped, half a dozen voices would shout out his name, and hands would beckon him to sit at the little tables under the trees and drink coffee. Policemen, peasants, and priests waved and smiled as he passed; fishermen, grocers, and café owners greeted him like a brother. ‘Ah, Spiro!’ they would say, and smile at him affectionately as though he were a naughty but lovable child. They respected his honesty and his belligerence, and above all they adored his typically Greek scorn and fearlessness when dealing with any form of governmental red tape. On arrival, two of our cases containing linen and other things had been confiscated by the customs on the curious grounds that they were merchandise. So, when we moved out to the strawberry-pink villa and the problem of bed linen arose, Mother told Spiro about our cases languishing in the customs, and asked his advice.

‘Gollys, Mrs Durrells,’ he bellowed, his huge face flushing red with wrath; ‘whys you never tells me befores? Thems bastards in the customs. I’ll take you down theres tomorrows and fix thems: I knows thems alls, and they knows me. Leaves everythings to me – I’ll fix thems.’

The following morning he drove Mother down to the customs shed. We all accompanied them, for we did not want to miss the fun. Spiro rolled into the customs house like an angry bear.

‘Wheres these peoples things?’ he inquired of the plump little customs man.

‘You mean their boxes of merchandise?’ asked the customs official in his best English.

‘Whats you thinks I means?’

‘They are here,’ admitted the official cautiously.

‘We’ve comes to takes thems,’ scowled Spiro; ‘gets thems ready.’

He turned and stalked out of the shed to find someone to help carry the luggage, and when he returned he saw that the customs man had taken the keys from Mother and was just lifting the lid of one of the cases. Spiro, with a grunt of wrath, surged forward and slammed the lid down on the unfortunate man’s fingers.

‘Whats fors you open it, you sonofabitch?’ he asked, glaring.

The customs official, waving his pinched hand about, protested wildly that it was his duty to examine the contents.

‘Dutys?’ said Spiro with fine scorn. ‘Whats you means, dutys? Is it your dutys to attacks innocent foreigners, eh? Treats thems like smugglers, eh? Thats whats yous calls dutys?’

Spiro paused for a moment, breathing deeply; then he picked up a large suitcase in each great hand and walked towards the door. He paused and turned to fire his parting shot.

‘I knows you, Christaki, sos donts you go talkings about dutys to me. I remembers when you was fined twelve thousand drachmas for dynamitings fish. I won’t have any criminal talkings to me abouts dutys.’

We rode back from the customs in triumph, all our luggage intact and unexamined.

‘Thems bastards thinks they owns the islands,’ was Spiro’s comment. He seemed quite unaware of the fact that he was acting as though he did.

Once Spiro had taken charge he stuck to us like a burr. Within a few hours he had changed from a taxi driver to our champion, and within a week he was our guide, philosopher, and friend. He became so much a member of the family that very soon there was scarcely a thing we did, or planned to do, in which he was not involved in some way. He was always there, bull-voiced and scowling, arranging things we wanted done, telling us how much to pay for things, keeping a watchful eye on us all and reporting to Mother anything he thought she should know. Like a great, brown, ugly angel he watched over us as tenderly as though we were slightly weak-minded children. Mother he frankly adored, and he would sing her praises in a loud voice wherever we happened to be, to her acute embarrassment.

‘You oughts to be carefuls whats you do,’ he would tell us, screwing up his face earnestly; ‘we donts wants to worrys your mothers.’

‘Whatever for, Spiro?’ Larry would protest in well-simulated astonishment. ‘She’s never done anything for us… why should we consider her?’

‘Gollys, Master Lorrys, donts jokes like that,’ Spiro would say in anguish.

‘He’s quite right, Spiro,’ Leslie would say very seriously; ‘she’s really not much good as a mother, you know.’

‘Donts says that, donts says that,’ Spiro would roar. ‘Honest to Gods, if I hads a mother likes yours I’d gos down every mornings and kisses her feets.’

So we were installed in the villa, and we each settled down and adapted ourselves to our surroundings in our respective ways. Margo, merely by donning a microscopic swim suit and sun-bathing in the olive groves, had collected an ardent band of handsome peasant youths who appeared like magic from an apparently deserted landscape whenever a bee flew too near her or her deck chair needed moving. Mother felt forced to point out that she thought this sun-bathing was rather unwise.

‘After all, dear, that costume doesn’t cover an awful lot, does it?’ she pointed out.

‘Oh, Mother, don’t be so old-fashioned,’ Margo said impatiently. ‘After all, you only die once.’

This remark was as baffling as it was true, and successfully silenced Mother.

It had taken three husky peasant boys half an hour’s sweating and panting to get Larry’s trunks into the villa, while Larry bustled round them, directing operations. One of the trunks was so big it had to be hoisted in through the window. Once they were installed, Larry spent a happy day unpacking them, and the room was so full of books that it was almost impossible to get in or out. Having constructed battlements of books round the outer perimeter, Larry would spend the whole day in there with his typewriter, only emerging dreamily for meals. On the second morning he appeared in a highly irritable frame of mind, for a peasant had tethered his donkey just over the hedge. At regular intervals the beast would throw out its head and let forth a prolonged and lugubrious bray.

‘I ask you! Isn’t it laughable that future generations should be deprived of my work simply because some horny-handed idiot has tied that stinking beast of burden near my window?’ Larry asked.

‘Yes, dear,’ said Mother, ‘why don’t you move it if it disturbs you?’

‘My dear Mother, I can’t be expected to spend my time chasing donkeys about the olive groves. I threw a pamphlet on Theosophy at it; what more do you expect me to do?’

‘The poor thing’s tied up. You can’t expect it to untie itself,’ said Margo.

‘There should be a law against parking those loathsome beasts anywhere near a house. Can’t one of you go and move it?’

‘Why should we? It’s not disturbing us,’ said Leslie.

‘That’s the trouble with this family,’ said Larry bitterly; ‘no give and take, no consideration for others.’

‘You don’t have much consideration for others,’ said Margo.

‘It’s all your fault, Mother,’ said Larry austerely; ‘you shouldn’t have brought us up to be so selfish.’

‘I like that!’ exclaimed Mother. ‘I never did anything of the sort!’

‘Well, we didn’t get as selfish as this without some guidance,’ said Larry.

In the end, Mother and I unhitched the donkey and moved it farther down the hill.

Leslie meanwhile had unpacked his revolvers and startled us all with an apparently endless series of explosions while he fired at an old tin can from his bedroom window. After a particularly deafening morning, Larry erupted from his room and said he could not be expected to work if the villa was going to be rocked to its foundations every five minutes. Leslie, aggrieved, said that he had to practise. Larry said it didn’t sound like practice, but more like the Indian Mutiny. Mother, whose nerves had also been somewhat frayed by the reports, suggested that Leslie practise with an empty revolver. Leslie spent half an hour explaining why this was impossible. At length he reluctantly took his tin farther away from the house where the noise was slightly muffled but just as unexpected.

In between keeping a watchful eye on us all, Mother was settling d

own in her own way. The house was redolent with the scent of herbs and the sharp tang of garlic and onions, and the kitchen was full of a bubbling selection of pots, among which she moved, spectacles askew, muttering to herself. On the table was a tottering pile of books which she consulted from time to time. When she could drag herself away from the kitchen, she would drift happily about the garden, reluctantly pruning and cutting, enthusiastically weeding and planting.

For myself, the garden held sufficient interest; together Roger and I learned some surprising things. Roger, for example, found that it was unwise to smell hornets, that the peasant dogs ran screaming if he glanced at them through the gate, and that the chickens that leaped suddenly from the fuchsia hedge, squawking wildly as they fled, were unlawful prey, however desirable.

This doll’s-house garden was a magic land, a forest of flowers through which roamed creatures I had never seen before. Among the thick, silky petals of each rose bloom lived tiny, crablike spiders that scuttled sideways when disturbed. Their small, translucent bodies were coloured to match the flowers they inhabited: pink, ivory, wine red, or buttery yellow. On the rose stems, encrusted with green flies, lady-birds moved like newly painted toys; lady-birds pale red with large black spots; lady-birds apple red with brown spots; lady-birds orange with grey-and-black freckles. Rotund and amiable, they prowled and fed among the anæmic flocks of greenfly. Carpenter bees, like furry, electric-blue bears, zigzagged among the flowers, growling fatly and busily. Humming bird hawk-moths, sleek and neat, whipped up and down the paths with a fussy efficiency, pausing occasionally on speed-misty wings to lower a long, slender proboscis into a bloom. Among the white cobbles large black ants staggered and gesticulated in groups round strange trophies: a dead caterpillar, a piece of rose petal or a dried grass-head fat with seeds. As an accompaniment to all this activity there came from the olive groves outside the fuchsia hedge the incessant shimmering cries of the cicadas. If the curious, blurring heat haze produced a sound, it would be exactly the strange, chiming cries of these insects.

At first I was so bewildered by this profusion of life on our very doorstep that I could only move about the garden in a daze, watching now this creature, now that, constantly having my attention distracted by the flights of brilliant butterflies that drifted over the hedge. Gradually, as I became more used to the bustle of insect life among the flowers, I found I could concentrate more. I would spend hours squatting on my heels or lying on my stomach watching the private lives of the creatures around me, while Roger sat nearby, a look of resignation on his face. In this way I learned a lot of fascinating things.

I found that the little crab spiders could change colour just as successfully as any chameleon. Take a spider from a wine-red rose, where he had been sitting like a bead of coral, and place him in the depths of a cool white rose. If he stayed there – and most of them did – you would see his colour gradually ebb away, as though the change had given him anæmia, until, some two days later, he would be crouching among the white petals like a pearl.

I discovered that in the dry leaves under the fuchsia hedge lived another type of spider, a fierce little huntsman with the cunning and ferocity of a tiger. He would stalk about his continent of leaves, eyes glistening in the sun, pausing now and then to raise himself up on his hairy legs to peer about. If he saw a fly settle to enjoy a sun-bath he would freeze; then, as slowly as a leaf growing, he would move forward, imperceptibly, edging nearer and nearer, pausing occasionally to fasten his life-line of silk to the surface of the leaves. Then, when close enough, the huntsman would pause, his legs shift minutely as he got a good purchase, and then he would leap, legs spread out in a hairy embrace, straight onto the dreaming fly. Never did I see one of these little spiders miss its kill, once it had manœuvred into the right position.

All these discoveries filled me with a tremendous delight, so that they had to be shared, and I would burst suddenly into the house and startle the family with the news that the strange, spiky black caterpillars on the roses were not caterpillars at all, but the young of lady-birds, or with the equally astonishing news that lacewing flies laid eggs on stilts. This last miracle I was lucky enough to witness. I found a lacewing fly on the roses and watched her as she climbed about the leaves, admiring her beautiful, fragile wings like green glass, and her enormous liquid golden eyes. Presently she stopped on the surface of a rose leaf and lowered the tip of her abdomen. She remained like that for a moment and then raised her tail, and from it, to my astonishment, rose a slender thread, like a pale hair. Then, on the very tip of this stalk, appeared the egg. The female had a rest, and then repeated the performance until the surface of the rose leaf looked as though it were covered with a forest of tiny club moss. The laying over, the female rippled her antennæ briefly and flew off in a mist of green gauze wings.

Perhaps the most exciting discovery I made in this multicoloured Lilliput to which I had access was an earwig’s nest. I had long wanted to find one and had searched everywhere without success, so the joy of stumbling upon one unexpectedly was overwhelming, like suddenly being given a wonderful present. I moved a piece of bark and there beneath it was the nursery, a small hollow in the earth that the insect must have burrowed out for herself. She squatted in the middle of it, shielding underneath her a few white eggs. She crouched over them like a hen, and did not move when the flood of sunlight struck her as I lifted the bark. I could not count the eggs, but there did not seem to be many, so I presumed that she had not yet laid her full complement. Tenderly I replaced her lid of bark.

From that moment I guarded the nest jealously. I erected a protecting wall of rocks round it, and as an additional precaution I wrote out a notice in red ink and stuck it on a pole nearby as a warning to the family. The notice read: ‘BEWAR – EARWIG NEST – QUIAT PLESE.’ It was only remarkable in that the two correctly spelled words were biological ones. Every hour or so I would subject the mother earwig to ten minutes’ close scrutiny. I did not dare examine her more often for fear she might desert her nest. Eventually the pile of eggs beneath her grew, and she seemed to have become accustomed to my lifting off her bark roof. I even decided that she had begun to recognize me, from the friendly way she waggled her antennæ.

To my acute disappointment, after all my efforts and constant sentry duty, the babies hatched out during the night. I felt that, after all I had done, the female might have held up the hatching until I was there to witness it. However, there they were, a fine brood of young earwigs, minute, frail, looking as though they had been carved out of ivory. They moved gently under their mother’s body, walking between her legs, the more venturesome even climbing onto her pincers. It was a heart-warming sight. The next day the nursery was empty: my wonderful family had scattered over the garden. I saw one of the babies some time later; he was bigger, of course, browner and stronger, but I recognized him immediately. He was curled up in a maze of rose petals, having a sleep, and when I disturbed him he merely raised his pincers irritably over his back. I would have liked to think that it was a salute, a cheerful greeting, but honesty compelled me to admit that it was nothing more than an earwig’s warning to a potential enemy. Still, I excused him. After all, he had been very young when I last saw him.

I came to know the plump peasant girls who passed the garden every morning and evening. Riding side-saddle on their slouching, drooping-eared donkeys, they were shrill and colourful as parrots, and their chatter and laughter echoed among the olive trees. In the mornings they would smile and shout greetings as their donkeys pattered past, and in the evenings they would lean over the fuchsia hedge, balancing precariously on their steeds’ backs, and, smiling, hold out gifts for me – a bunch of amber grapes still sun-warmed, some figs black as tar striped with pink where they had burst their seams with ripeness, or a giant watermelon with an inside like pink ice. As the days passed, I came gradually to understand them. What had at first been a confused babble became a series of recognizable separate sounds. Then, suddenly, these took on mean

ing, and slowly and haltingly I started to use them myself; then I took my newly acquired words and strung them into ungrammatical and stumbling sentences. Our neighbours were delighted, as though I had conferred some delicate compliment by trying to learn their language. They would lean over the hedge, their faces screwed up with concentration, as I groped my way through a greeting or a simple remark, and when I had successfully concluded they would beam at me, nodding and smiling, and clap their hands. By degrees I learned their names, who was related to whom, which were married and which hoped to be, and other details. I learned where their little cottages were among the olive groves, and should Roger and I chance to pass that way the entire family, vociferous and pleased, would tumble out to greet us, to bring a chair, so that I might sit under their vine and eat some fruit with them.

Gradually the magic of the island settled over us as gently and clingingly as pollen. Each day had a tranquillity, a timelessness, about it, so that you wished it would never end. But then the dark skin of night would peel off and there would be a fresh day waiting for us, glossy and colourful as a child’s transfer and with the same tinge of unreality.

3

The Rose-Beetle Man

In the morning, when I woke, the bedroom shutters were luminous and barred with gold from the rising sun. The morning air was full of the scent of charcoal from the kitchen fire, full of eager cock-crows, the distant yap of dogs, and the unsteady, melancholy tune of the goat bells as the flocks were driven out to pasture.

We ate breakfast out in the garden, under the small tangerine trees. The sky was fresh and shining, not yet the fierce blue of noon, but a clear milky opal. The flowers were half asleep, roses dew-crumpled, marigolds still tightly shut. Breakfast was, on the whole, a leisurely and silent meal, for no member of the family was very talkative at that hour. By the end of the meal the influence of the coffee, toast, and eggs made itself felt, and we started to revive, to tell each other what we intended to do, why we intended to do it, and then argue earnestly as to whether each had made a wise decision. I never joined in these discussions, for I knew perfectly well what I intended to do, and would concentrate on finishing my food as rapidly as possible.

A Zoo in My Luggage

A Zoo in My Luggage The New Noah

The New Noah The Bafut Beagles

The Bafut Beagles Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Catch Me a Colobus

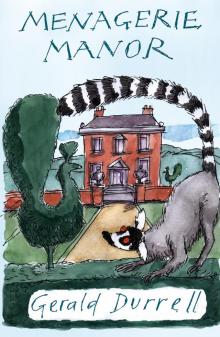

Catch Me a Colobus Menagerie Manor

Menagerie Manor The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Ark on the Move

Ark on the Move My Family and Other Animals

My Family and Other Animals Two in the Bush (Bello)

Two in the Bush (Bello) The Stationary Ark

The Stationary Ark The Whispering Land

The Whispering Land Three Singles to Adventure

Three Singles to Adventure Fillets of Plaice

Fillets of Plaice The Aye-Aye and I

The Aye-Aye and I Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons

Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons The Drunken Forest

The Drunken Forest Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories

Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy)

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) The Corfu Trilogy

The Corfu Trilogy Marrying Off Mother

Marrying Off Mother Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush