- Home

- Gerald Durrell

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Page 4

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Read online

Page 4

‘I wouldn’t mind if you had had the decency to tell me in advance. I could, at least, have risked death travelling by air’, said my elder brother, Larry, looking despondently at one of the many glasses that an irritatingly happy waiter had put in front of him. ‘But what in heaven’s name possessed you to go and book us all on a Greek ship for three days? I mean, it’s as stupid as deliberately booking on the Titanic.’

‘I thought it would be more cheerful, and the Greeks are such good sailors; replied my mother, defensively. ‘Anyway, it’s her maiden voyage.’

You always cry wolf before you’re hurt; put in Margo. ‘I think it was a brilliant idea of Mother’s.’

‘I must say, I agree with Larry,’ said Leslie, with the obvious reluctance that we all shared in agreeing with our elder brother. We all know what Greek ships are like:

‘Not all of them, dear; said Mother. ‘Some of them must be all right.’

‘Well, there’s damn all we can do about it now,’ concluded Larry gloomily. ‘You’ve committed us to sail on this bloody craft, which I have no doubt would have been rejected by the Ancient Mariner in his cups.’

‘Nonsense, Larry,’ said Mother. ‘You always exaggerate. The man at Cook’s spoke very highly of it.’

‘He said the bar was full of life; cried Margo triumphantly.

‘God almighty,’ exclaimed Leslie.

‘And to dampen our pagan spirits,’ agreed Larry, ‘the most revolting selection of Greek wines, which all taste as though they have been forced from the reluctant jugular vein of some hermaphrodite camel.’

‘Larry, don’t be so disgusting,’ said Margo.

‘Look,’ protested Larry vehemently, ‘I have been dragged away from France on this ill-fated attempt to revisit the scenes of our youth, much against my better judgement. Already I am beginning to regret it, and we’ve only just got as far as Venice, for God’s sake. Already I’m curdling what remains of my liver with Lacrima Christi instead of good, honest Beaujolais. Already my senses have been assaulted in every restaurant by great mounds of spaghetti, like some sort of awful breeding ground for tapeworms, instead of Charolais steaks:

‘Larry, I do wish you wouldn’t talk like that,’ said my mother. ‘There’s no need for vulgarity.’

In spite of the three bands, all playing different tunes at different corners of the great square, the vocalization of the Italians and tourists, and the sleepy crooning of the somnambulistic pigeons, it seemed that half of Venice was listening, entranced, to our private family row.

‘It will be perfectly all right when we are on board,’ said Margo. ‘After all, we will be among the Greeks.’

‘I think that’s what Larry’s worried about,’ commented Leslie gloomily.

‘Well,’ said Mother, trying to introduce an air of false confidence into the proceedings, ‘we should be going. Taking one of those vaporiser things down to the docks.’

We paid our bill, straggled down to the Canal and climbed on board one of the motor launches which my mother, with her masterly command of Italian, insisted on calling a vaporiser. The Italians, being less knowledgeable, called them vaporettos. Venice was a splendid sight as we chugged our way down the Canal, past the great houses, past the rippling reflections of the lights in the water. Even Larry had to admit that it was a slight improvement on the Blackpool illuminations. We were landed eventually at the docks, which, like docks everywhere in the world, looked as though they had been designed (in an off moment) by Dante while planning his Inferno. We huddled in puddles of phosphorescent light that made us all look like something out of an early Hollywood horror film and completely destroyed the moonlight, which was by now silver as a spider’s web. Our gloom was not even lightened by the sight of Mother’s diminutive figure attempting to convince three rapacious Venetian porters that we did not need any help with our motley assortment of luggage. It was an argument conducted in basic English.

‘We English. We no speak Italian,’ she cried in tones of despair, adding a strange flood of words which consisted of Hindustani, Greek, French and German, none of which bore any relation to each other. This was my mother’s way of communication with any foreigner, be they Aborigine or Eskimo, but it failed to do more than momentarily lighten our gloom.

We stood and contemplated those bits of the Canal which led out into our section of the dock. Suddenly there slid into view a ship which, even by the most land-lubberish standards, could never have been mistaken for seaworthy. At sometime in her career, she had been used as a species of reasonably sized inshore steamer but even in those days, when she had been virginal and freshly painted, she could not have been beautiful. Now, sadly lacking in any of the trappings that, in that ghastly phosphorescent light, might have made her turn into a proud ship, there was nothing. Fresh paint had not come her way for a number of years and there were large patches of rust, like unpleasant sores and scabs, all along her sides. Like a woman on excessively high-heeled shoes who had had the misfortune to lose one of the heels, she had a heavy list to starboard. Her totally unkempt air was bad enough, but the final indignity was exposed as she turned to come alongside the docks. It was an enormous tattered hole in her bows that would have admitted a pair of Rolls-Royces side by side. This terrible defloration was made worse by the fact that no first-aid of any description, even of the most primitive kind, had been attempted. The plates on her hull curved inwards where they had been crushed, like a gigantic chrysanthemum. Struck dumb, we watched her come alongside; there, above the huge hole in her bows, was her name: the Poseidon.

‘Dear God!’ breathed Larry.

‘She’s appalling,’ said Leslie, the more nautical member of our family. ‘Look at that list.’

‘But it’s our boat,’ squeaked Margo. ‘Mother, it’s our boat!’

‘Nonsense, dear, it can’t be,’ said my mother, readjusting her spectacles and peering hopefully up at the boat as it loomed above us.

‘Three days on this,’ said Larry. ‘It will be worse than the Ancient Mariner’s experience, mark my words.’

‘I do hope they are going to do something about that hole,’ said Mother worriedly, ‘before we put out to sea.’

‘What do you expect them to do? Stuff a blanket into it?’ asked Larry.

‘But surely the Captain’s noticed it,’ said Mother bewildered.

‘I shouldn’t think that even a Greek captain could have been oblivious of the fact that they have, quite recently, given something a fairly sharp tap,’ said Larry.

‘The waves will get in,’ moaned Margo. ‘I don’t want waves in my cabin. My dresses will all be ruined.’

‘I should think all the cabins are under water by now,’ observed Leslie.

‘Our snorkels and flippers will come in handy,’ said Larry. ‘What a novelty to have to swim down to dinner. How I shall enjoy it all.’

‘Well, as soon as we get on board you must go up and have a word with the Captain,’ decided Mother. ‘It’s just possible that he wasn’t on board when it happened, and no one’s told him.’

‘Really, Mother, you do annoy me,’ said Larry irritably. ‘What do you expect me to say to the man? “Pardon me, Kyrie Capitano, sir, but did you know you’ve got death-watch beetle in your bows?” ’

‘Larry, you always complicate things,’ complained Mother. ‘You know I can’t speak Greek or I’d do it.’

‘Tell him I don’t want waves in my cabin,’ insisted Margo.

‘As we are due to leave tonight, they couldn’t possibly mend it anyway,’ observed Leslie.

‘Exactly,’ said Larry. ‘But Mother seems to think that I am some sort of reincarnation of Noah.’

‘Well, I shall have something to say about it when I get on board,’ said Mother belligerently, as we made our way up the gangway.

At the head of the gangway, we were met by a rom

antic-looking Greek steward (with eyes as soft and melting as black pansies) wearing a crumpled and off-grey white suit, with most of the buttons missing. From his tarnished epaulettes, he appeared to be the Purser, and his smiling demand for passports and tickets was so redolent of garlic that Mother reeled back against the rails, her query about the ship’s bows stifled.

‘Do you speak English?’ asked Margo, gamely rallying her olfactory nerves more rapidly than Mother.

‘Small,’ he replied, bowing.

‘Well, I don’t want waves in my cabin,’ said Margo firmly. ‘It will ruin my clothes.’

‘Everything you want we give,’ he answered. ‘If you want wife, I give you my wife. She . . .’

‘No, no,’ exclaimed Margo, ‘the waves. You know . . . water?’

‘Every cabeen has having hot and cold running showers,’ he said with dignity. ‘Also there is bath or nightcloob having dancing and wine and water.’

‘I do wish you’d stop laughing and help us, Larry,’ said Mother, covering her nose with her handkerchief to repel the odour of garlic, which was so strong that one got the impression it was like a shimmering cloud round the Purser’s head.

Larry pulled himself together and in fluent Greek (which delighted the Purser) elicited, in rapid succession, the information that the ship was not sinking, that there were no waves in the cabins, and that the Captain knew all about the accident as he had been responsible for it. Wisely, Larry did not pass on this piece of information to Mother. While Mother and Margo were taken in a friendly and aromatic manner down to the cabins by the Purser, the rest of us then followed his instructions as to how to get to the bar.

This, when we located it, made us all speechless. It looked like the mahogany-lined lounge of one of the drearier London clubs. Great chocolate-coloured leather chairs and couches cluttered the place, interspersed with formidable fumed-oak tables. Dotted about were huge Benares brass bowls in which sprouted tattered, dusty palm trees. There was, in the midst of this funereal splendour, a minute parquet floor for dancing, flanked on one side by the small bar containing a virulent assortment of drinks, and on the other by a small raised dais, surrounded by a veritable forest of potted palms. In the midst of this, enshrined like flies in amber, were three lugubrious musicians in frock coats, celluloid dickies, and cummerbunds that would have seemed dated in about 1890. One played on an ancient upright piano and tuba, one played a violin with much professional posturing, and the third doubled up on the drums and trombone. As we entered, this incredible trio was playing ‘The Roses of Picardy’ to an entirely empty room.

‘I can’t bear it,’ said Larry. ‘This is not a ship; it’s a sort of floating Cadena Café from Bournemouth. It’ll drive us all mad.’

At Larry’s words, the band stopped playing and the leader’s face lit up in a gold-toothed smile of welcome. He gestured at his two colleagues with his bow and they also bowed and smiled. We three could do no less, and so we swept them a courtly bow before proceeding to the bar. The band launched itself with even greater frenzy into ‘The Roses of Picardy’ now that it had an audience.

‘Please give me,’ Larry asked the barman, a small wizened man in a dirty apron, ‘in one of the largest glasses you possess, an ouzo that will, I hope, paralyse me.’

The barman’s walnut face lit up at the sound of a foreigner who could not only speak Greek but was rich enough to drink so large an ouzo.

‘Amessos, kyrie,’ he said. ‘Will you have it with water or ice?’

‘One lump of ice,’ Larry stipulated. ‘Just enough to blanch its cheeks.’

‘I’m sorry, kyrie, we have no ice,’ said the barman, apologetically.

Larry sighed a deep and long-suffering sigh.

‘It is only in Greece,’ he said to us in English, ‘that one has this sort of conversation. It gives one the feeling that one is in such close touch with Lewis Carroll that the barman might be the Cheshire cat in disguise.’

‘Water, kyrie?’ asked the barman, sensing from Larry’s tone that he was not receiving approbation but rather censure.

‘Water,’ said Larry, in Greek, ‘a tiny amount.’

The barman went to the massive bottle of ouzo, as clear as gin, poured out a desperate measure, and then went to the little sink and squirted water in from the tap. Instantly, the ouzo turned the colour of watered milk and we could smell the aniseed from where we were standing.

‘God, that’s a strong one,’ said Leslie. ‘Let’s have the same.’

I agreed. The glasses were set before us. We raised them in toast!

‘Well, here’s to the Marie Celeste and all the fools who sail in her,’ said Larry, and took a great mouthful of ouzo. The next minute he spat it out in a flurry that would have done credit to a dying whale, and reeled back against the bar, clasping his throat, his eyes watering.

‘Ahhh!’ he roared. ‘The bloody fool’s put bloody hot water in it!’

Nurtured as we had been among the Greeks, we were inured to the strange behaviour they indulged in, but for a Greek to put boiling water in his national drink, was, we felt, carrying eccentricity too far.

‘Why did you put hot water in the ouzo?’ asked Leslie belligerently.

‘Because we have no cold,’ said the barman, surprised that Leslie should not have worked out this simple problem in logic for himself. ‘That is why we have no ice. This is the maiden voyage, kyrie, and that is why we have nothing but hot water in the bar.’

‘I don’t believe it,’ said Larry brokenly. ‘I just don’t believe it. A maiden voyage and the ship’s got a bloody great hole in her bows, a Palm Court Orchestra of septuagenarians, and nothing but hot water in the bar.’

At that moment Mother appeared, looking distinctly flustered.

‘Larry, I want to speak to you,’ she panted.

Larry looked at her. ‘What have you found? An iceberg in the bunk?’ he asked.

‘Well, there’s a cockroach in the cabin. Margo threw a bottle of Eau de Cologne at it, and it broke, and now the whole place smells like a hairdresser’s. I don’t think it killed the cockroach either,’ said Mother.

‘Well,’ rejoined Larry. ‘I’m delighted you have been having fun. Have a red-hot ouzo to round off the start of this riotous voyage!

‘No, I didn’t come here to drink.’

‘You surely didn’t come to tell me about an Eau de Cologne-drenched cockroach?’ asked Larry in surprise. ‘Your conversation is getting worse than the Greeks for eccentricity:

‘No, it’s Margo,’ Mother hissed. ‘She went to the you-know-where and she’s got the slot jammed.’

‘The “you-know-where”? Where’s that?’

‘The lavatory, of course. You know perfectly well what I mean.’

‘I don’t know what you expect me to do,’ said Larry. ‘I’m not a plumber.’

‘Can’t she climb out?’ enquired Leslie.

‘No,’ said Mother. ‘She’s tried, but the hole at the top is much too small, and so is the hole at the bottom.’

‘But at least there are holes,’ Larry pointed out. ‘You need air in a Greek lavatory in my experience and we can feed her through them during the voyage.’

‘Don’t be so stupid, Larry’ said Mother. ‘You’ve got to do something.’

‘Try putting another coin in the slot thing,’ suggested Leslie. ‘That sometimes does it.’

‘I did,’ said Mother. ‘I put a lira in but it still wouldn’t work.’

‘That’s because it’s a Greek lavatory and will only accept drachmas,’ Larry pointed out. ‘Why didn’t you try a pound note? The rate of exchange is in its favour.’

‘Well, I want you to get a stewardess to help her out,’ said Mother. ‘She’s been in there ages. She can’t stay all night. Supposing she banged her elbow and fainted? You know she’s a

lways doing that.’ Mother tended to look on the black side of things.

‘In my experience of Greek lavatories,’ said Larry judiciously, ‘you generally faint immediately upon entering without the need to bang your elbow.’

‘Well, for heaven’s sake do something!’ cried Mother. ‘Don’t just stand there drinking.’

Led by her, we eventually found the lavatory in question. Leslie, striding in masterfully, rattled the door.

‘Me stuck. Me English,’ shouted Margo from behind the door. ‘You find stewardess.’

‘I know that, you fool. It’s me, Leslie,’ he growled.

‘Go out at once. It’s a ladies’ lavatory,’ said Margo.

‘Do you want to get out or not? If you do, shut up!’ retorted Leslie belligerently.

He fiddled ineffectually with the door, swearing under his breath.

‘I do wish you wouldn’t use bad language, dear,’ protested Mother. ‘Remember, you are in the ladies’.’

‘There should be a little knob thing on the inside which you pull,’ said Leslie. ‘A sort of bolt thing.’

‘I’ve pulled everything,’ rejoined Margo indignantly. ‘What do you think I’ve been doing in here for the last hour?’

‘Well, pull it again,’ suggested Leslie, ‘while I push.’

‘All right, I’m pulling,’ said Margo.

Leslie humped his powerful shoulders and threw himself at the door.

‘It’s like a Pearl White serial,’ said Larry, sipping the ouzo that he had thoughtfully brought with him and which had by now cooled down. ‘If you’re not careful we’ll have another hole in the hull.’

A Zoo in My Luggage

A Zoo in My Luggage The New Noah

The New Noah The Bafut Beagles

The Bafut Beagles Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Catch Me a Colobus

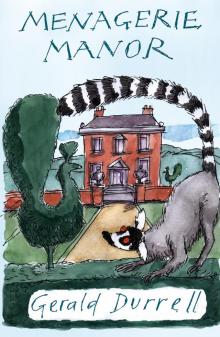

Catch Me a Colobus Menagerie Manor

Menagerie Manor The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Ark on the Move

Ark on the Move My Family and Other Animals

My Family and Other Animals Two in the Bush (Bello)

Two in the Bush (Bello) The Stationary Ark

The Stationary Ark The Whispering Land

The Whispering Land Three Singles to Adventure

Three Singles to Adventure Fillets of Plaice

Fillets of Plaice The Aye-Aye and I

The Aye-Aye and I Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons

Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons The Drunken Forest

The Drunken Forest Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories

Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy)

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) The Corfu Trilogy

The Corfu Trilogy Marrying Off Mother

Marrying Off Mother Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush