- Home

- Gerald Durrell

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Page 7

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Read online

Page 7

‘Papadopoulos!’ he roared at the poor Chief Officer, who was getting shakily to his feet and mopping blood from his nose, ‘you son of a poutana, you imbecile, you donkey! You illegitimate son of a ditch-delivered Turkish cretin! Why didn’t you lower the anchor?’

‘But Captain,’ began the Chief Officer, his voice muffled behind a blood-stained handkerchief, ‘you never told me to.’

‘Am I expected to do everything around here,’ bellowed the Captain. ‘Steer the ship, run the engines, produce the band which can play the Greek songs? Mother of God!’ He clapped his face in his hands.

All around arose the cacophony of Greeks in a SITUATION. With this noise, and the Captain’s tragic figure, it seemed rather like a scene from the battle of Trafalgar.

‘Well,’ said Larry, mopping blood from his eyes, ‘this was a splendid idea, Mother. I do congratulate you. I think, however, I will fly back. That is, if we can get ashore alive.’

Eventually, the walking wounded were allowed ashore and we straggled down the gangway. We could now see that the Poseidon had another, almost identical, hole in her bows, on the opposite side to the previous one.

‘Well, at least now she matches,’ said Leslie gloomily.

‘Oh, look!’ said Margo, as we stood on the docks. ‘There’s that poor old band.’

She waved, and the three old gentlemen bowed. We saw that the violinist had a nasty cut on his forehead and the tuba player a piece of sticking plaster across the bridge of his nose. They returned our bows and, obviously interpreting the appearance of the family as a sign of support that would do something to restore their sense of dignity which had been so sorely undermined by their ignominious dismissal of the night before, they turned in unison, glanced up at the bridge, with looks of great defiance raised tuba, trombone and violin, and started to play.

The strains of ‘Never on Sunday’ floated down to us.

The Public School Education

Venice is one of the most beautiful of European cities and one that I had visited frequently but never stayed in. I had always been on my way to somewhere else and so had never had the time for proper exploration. So, one red-hot summer when I had been working hard and was feeling tired and in need of a change, I decided that I would go and spend a week in Venice and relax and get to know her. I felt that a calming holiday in such a setting was exactly what I needed. I have rarely regretted a decision more; if I had known what was going to happen to me I would have fled to New York or Buenos Aires or Singapore rather than set foot in that most elegant of cities.

I drove through the beautiful and incomparable France, through orderly Switzerland, over the high passes where there were still ugly piles of dirty grey snow at the edge of the roads and then down into Italy and towards my destination. The weather remained perfect until I reached the causeway that leads into Venice. Here the sky, with miraculous suddenness, turned from blue to black, became veined with fern-like threads of intense blue and white lightning, and then disgorged a torrent of rain of such magnitude that it made windscreen wipers futile and brought a great chain of traffic to a standstill. Hundreds of hysterically twitching Italians sat there, nose to tail, immobilized by the downpour, trying to ease their frustration by blowing their horns cacophonously, and screaming abuse at each other above the roar of the rain.

At length, edging forward inch by inch I finally managed to get the car to the garage at the end of the causeway. Having successfully berthed her, I found myself a burly porter to carry my bags. At a run we galloped through the teeming rain to the docks where the speedboat belonging to the hotel into which I had booked lay waiting. My suitcases were drenched with rain, and by the time they had been put on board the boat, and I had tipped the porter and got on board myself, my thin tropical suit was a limp, damp rag. The moment, however, that the speedboat started up the rain died down to a very fine, drifting mizzle which hung across the canals like a fine veil of lawn, muting the russets and browns and pinks of the buildings so that they looked like a beautifully faded Canaletto painting.

We sped down the Grand Canal and when we reached my hotel the boat put into the hotel jetty. As the engine stuttered and died we were passed by a gondola, propelled in a rather disconsolate fashion by a very damp-looking gondolier. The two people occupying it were shielded from the inclemencies of the weather by a large umbrella and so I could not see their faces, but, as the gondola passed us and sped down a narrow side canal that led to Marco Polo’s house, I heard a penetrating female English voice (obviously the product of Roedean, that most expensive of public schools), float out from under the umbrella.

‘Of course, Naples is just like Venice only without so much water,’ it observed in flute-like tones.

I stood riveted on the landing stage outside the hotel, staring after the retreating gondola. Surely, I said to myself, I must be dreaming, and yet in my experience there was only one voice in the world like that; only one voice, moreover, capable of making such a ridiculous statement. It belonged to a girlfriend of mine whom I had not seen for some thirty years, Ursula Pendragon-White. She, of all my girlfriends, I think I adored the most, but she was also the one who filled me with the most alarm and despondency.

It was not only her command over the English language that caused me pain (it was she who had told me about a friend of hers who had had an ablution so she would not have an illegitimate baby), but her interference in the private lives of her wide circle of acquaintances. When I had last known her she was busy trying to reform a friend of hers who, she said, was drinking so much that he was in danger of becoming an incoherent.

But no, I thought to myself, it could not be Ursula. She was safely and happily married to a very dull young man and lived in the depths of Hampshire. What on earth would she be doing in Venice at a time of year when all good farmers’ wives were helping their husbands get the harvest in, or organizing jumble sales in the village. In any case, I thought to myself, even if it was Ursula I did not want to get tangled up with her again. I had come here for peace and quiet, and from my past experience of her I knew that close contact with her brought anything but that. Speaking as one who had had to pursue a Pekinese puppy through a crowded theatre during a Mozart concert, I knew that Ursula could get one involved in the most horrifying of predicaments without even really trying. No, no, I thought, it could not have been Ursula, and even if it had been thank God she had not spotted me.

The hotel was sumptuous and my large and ornate bedroom overlooking the Grand Canal was exceedingly comfortable. After I had changed out of my wet things and had a bath and a drink I saw that the weather had changed and the sun was blazing, making the whole of Venice glitter in a delicate sunset of colours. I walked down numerous little alleyways, crossed tiny bridges over canals, until I came at length to the vast Piazza San Marco, lined with bars, each of which had its own orchestra. Hundreds of pigeons wheeled and swooped through the brilliant air as people purchased bags of corn and scattered this largess for the birds on to the mosaic of the huge square. I picked my way through the sea of birds until I reached the Doge’s Palace where there was a collection of pictures that I wanted to see. The Palace was crammed with hundreds of sightseers of a dozen different nationalities, from Japanese, festooned like Christmas trees with cameras, to portly, guttural Germans and lithe blond Swedes. Wedged in this human lava flow I progressed slowly from room to room, admiring the paintings. Suddenly I heard the penetrating flute-like voice up ahead of me in the crowd.

‘Last year, in Spain,’ it said, ‘I went to see all those pictures by Gruyére . . . so gloomy, with lots of corpses and things. So depressing, not like these. I really do think that Cannelloni is positively my favourite Italian painter. Scrumptious!’

Now I knew, beyond a shadow of doubt, that it was Ursula. No other woman would be capable of getting a cheese, a pasta and two painters so inextricably entwined. I shifted cautiously through the

crowd until I could see her distinctive profile, the large brilliant blue eyes, the long tip-tilted nose, the end of which looked as if it had been snipped off – an enchanting effect – and her cloud-like mass of hair still, to my surprise, dark, but with streaks of silver in it. She looked as lovely as ever and the years had dealt kindly with her.

She was with a middle-aged, very bewildered-looking man, who was gazing at her in astonishment at her culinary-artistic observation. I felt, from his amazement, that he must be a comparatively new acquaintance, for anyone who had known Ursula for any length of time would take her last statement in his stride.

Beautiful and enchanting though she was, I felt it would be safer for my peace of mind not to renew my acquaintance with her lest something diabolical resulted to ruin my holiday. Reluctantly, I left the Palace, determined to come back the following day when I felt Ursula would have had her fill of pictures. I made my way back into the Piazza San Marco, found a pleasant café and sat down to a well-earned brandy and soda. All the cafes around the square were packed with people and in such a crowd I was, I felt, certain to escape observation. In any case I was sure Ursula would not recognize me, for I was several stone heavier than when she had last seen me, my hair was grey and I now sported a beard.

Feeling safe, I sat there to enjoy my drink and listen to the charming Strauss waltzes the band was playing. The sunshine, my pleasant drink and the soothing music lulled me into a sense of false security. I had forgotten Ursula’s ability – a sense well developed in most women but in her case enlarged to magical proportion – to walk into a crowded room, take one glance around in a casual way and then be able to tell you, not only who was in the room but what they were all wearing. So I shouldn’t have felt the shock and surprise I did when I suddenly heard her scream above the chatter of the crowd and the noise of the band.

‘Darling, darling,’ she cried, hurrying through the tables towards me. ‘Darling Gerry, it’s me, Ursula!’

I rose to meet my fate. Ursula rushed into my arms, fastened her mouth on mine and gave me a prolonged kiss accompanied by humming noises, of the sort that (even in this permissive day and age) were of the variety which one generally reserved for the bedroom. Presently, when I began to think that we might be arrested by the Italian police for disorderly behaviour, Ursula dragged her mouth reluctantly away from mine and stood back, holding tightly on to my hands.

‘Darling,’ she cooed, her huge blue eyes brimming with tears of delight, ‘darling . . . I can’t believe it . . . seeing you again after all these years . . . it’s a miracle . . . oh, I am so happy, darling. How scrumptious to see you again.’

‘How did you know it was me?’ I asked feebly.

‘How did I know, darling? You, are silly . . . you haven’t changed a bit,’ she said untruthfully. ‘Besides, darling, I’ve seen you on television and your photos on the covers of your books, so naturally I would recognize you.’

‘Well, it’s very nice to see you again,’ I went on guardedly.

‘Darling, it’s been simply an age,’ she said, ‘far too long.’

She had, I noticed, divested herself of the bewildered-looking gentleman.

‘Sit down and have a drink,’ I suggested.

‘Of course, sweetie, I’d love one.’ She seated herself, willowy and elegant, at my table. I beckoned the waiter.

‘What are you drinking?’ she asked.

‘Brandy and soda.’

‘Ugh!’ she cried, shuddering delicately. ‘How positively revolting. You shouldn’t drink it, darling, you’ll end up with halitosis of the liver.’

‘Never mind my liver,’ I said, long-sufferingly. ‘What do you want to drink?’

‘I’ll have one of those Bonny Prince Charlie things.’

The waiter stared at her blankly. He did not have the benefit of my early training with Ursula.

‘Madam would like a Dubonnet,’ I said, ‘and I’ll have another brandy.’

I sat down at the table and Ursula leant forward, gave me a ravishing, melting smile and seized my hand in both of hers.

‘Darling, isn’t this romantic?’ she asked. ‘You and me meeting after all these years in Venice? It’s the most romantic thing I’ve heard of, don’t you think?’

‘Yes,’ I said cautiously, ‘how’s your husband?’

‘Oh, didn’t you know? I’m divorced.’

‘I’m sorry’.

‘Oh, it’s all right,’ she explained. ‘It was better really. You see, poor dear, he was never the same after he got foot and mouth disease.’

Even my previous experience of Ursula had not prepared me for this.

‘Toby got foot and mouth disease?’ I asked.

‘Yes . . . terribly’ she said with a sigh, ‘and he was never really the same again.’

‘I should think not. But surely cases of humans getting it must be very rare?’

‘Humans?’ she said, wide-eyed. ‘What d’you mean?’

‘Well, you said that Toby . . ., I began, when Ursula gave a shriek of laughter.

‘You are silly,’ she crowed. ‘I meant that all his cattle got it. His whole pedigree herd that had taken him years to breed. He had to kill the lot, and it seemed to affect him a lot, poor lamb. He started going about with the most curious women and getting drunk in night clubs and that sort of thing.’

‘I never realized that foot and mouth disease could have such far-reaching effects,’ I said. ‘I wonder if the Ministry of Agriculture knows?’

‘D’ you think they’d be interested?’ Ursula asked in astonishment. ‘I could write to them about it if you thought I ought to.’

‘No, no,’ I said, hastily, ‘I was only joking.’

‘Well,’ she said, ‘tell me about your marriage.’

‘I’m divorced, too,’ I confessed.

‘You are? Darling, I told you this meeting was romantic,’ she said misty-eyed. ‘The two of us meeting in Venice with broken marriages. It’s just like a book, darling.’

‘Well, I don’t think we ought to read too much into it.’

‘What are you doing in Venice?’ she asked.

‘Nothing,’ I said, unguardedly. ‘I’m just here for a holiday’

‘Oh, wonderful, darling, then you can help me,’ she exclaimed.

‘No!’ I said hastily, ‘I won’t help you.’

‘Darling, you don’t even know what I’m asking you to do,’ she said plaintively.

‘I don’t care what it is, I’m not doing it.’

‘Sweetie, this is the first time we’ve met in ages and you’re being horrid to me before we even start,’ she said indignantly.

‘I don’t care. I know all about your machinations from bitter experience and I do not intend to spend my holiday getting mixed up with whatever awful things you are doing.’

‘You’re beastly’ she said, her eyes brimming, blue as flax flowers, her red mouth quivering. ‘You’re perfectly beastly . . . here am I alone in Venice, without a husband, and you won’t lift a finger to help me in my distress. You’re revolting and unchivalrous . . . and . . . beastly.’

I groaned. ‘Oh, all right, all right, tell me about it. But I warn you I’m not getting involved. I came here for peace and quiet.’

‘Well,’ said Ursula, drying her eyes and taking a sip of her drink, ‘I’m here on what you might call an errand of mercy. The whole thing is fraught with difficulty and imprecations.’

‘Imprecations?’ I asked, fascinated in spite of myself.

Ursula looked around to make sure we were alone. As we were only surrounded by some five thousand junketing foreigners she felt it was safe to confide in me.

‘Imprecations in high places,’ she said, lowering her voice. ‘It’s something you must not let go any further.’

‘Don’t you

mean implications?’ I asked, wanting to get the whole thing on to a more or less intelligible plane.

‘I mean what I say,’ said Ursula frostily. ‘I do wish you’d stop trying to correct me.’ It was one of your worst characteristics in the old days that you would go on and on correcting me. It’s very irritating, darling.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I said contritely, ‘do go on and tell me who in high places is imprecating whom.’

‘Well,’ she said, lowering her voice to such an extent that I could hardly hear her in the babble of noise that surrounded us, ‘it involves the Duke of Tolpuddle. That’s why I’ve had to come to Venice because I’m the only one Reggie and Marjorie will trust and Perry, too, for that matter, and of course the Duke who is an absolute sweetie and is naturally so cut up about the whole thing, what with the scandal and everything, and so naturally when I said I’d come they jumped at it. But you mustn’t say a word about it to anyone, darling, promise?’

‘What am I not to say a word about?’ I asked, dazedly, signalling the waiter for more drinks.

‘But I’ve just told you,’ said Ursula impatiently. ‘About Reggie and Marjorie and Perry. And, of course, the Duke.’

I took a deep breath: ‘But I don’t know Reggie and Marjorie and Perry or the Duke.’

‘You don’t?’ asked Ursula, amazed.

I remembered then that she was always astonished to find that you did not know everyone in her wide circle of incredibly dull acquaintances.

‘No. So, as you will see, it is difficult for me to understand the problem. As far as I am aware, it may range from them all having developed leprosy to the Duke being caught operating an illicit still.’

‘Don’t be silly, darling,’ said Ursula, shocked. ‘There’s no insanity in the family.’

I sighed. ‘Look, just tell me who did what to whom, remembering that I don’t know any of them, and I have a feeling that I don’t want to.’

A Zoo in My Luggage

A Zoo in My Luggage The New Noah

The New Noah The Bafut Beagles

The Bafut Beagles Encounters With Animals

Encounters With Animals Catch Me a Colobus

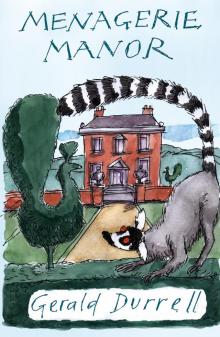

Catch Me a Colobus Menagerie Manor

Menagerie Manor The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium

The Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium Ark on the Move

Ark on the Move My Family and Other Animals

My Family and Other Animals Two in the Bush (Bello)

Two in the Bush (Bello) The Stationary Ark

The Stationary Ark The Whispering Land

The Whispering Land Three Singles to Adventure

Three Singles to Adventure Fillets of Plaice

Fillets of Plaice The Aye-Aye and I

The Aye-Aye and I Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons

Golden Bats & Pink Pigeons The Drunken Forest

The Drunken Forest Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories

Marrying Off Mother: And Other Stories The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy)

The Corfu Trilogy (the corfu trilogy) The Corfu Trilogy

The Corfu Trilogy Marrying Off Mother

Marrying Off Mother Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush